There were a number of ways in which Scottish medicine at this time was distinctly different from that of England and elsewhere in Europe.

In Edinburgh, the infirmary maintained close ties with the university - which enabled medical students to learn from practical experience as well as theory. Students in Scotland could study a range of medical subjects within one university – helping to make them general practitioners. They could pick and choose individual classes which interested them (rather than necessarily studying a full degree) and learn in English, as the use of Latin was being phased out at Scottish universities.

Anatomy and surgery: the migration to London

Two of the most cited examples are the anatomist brothers John and William Hunter. In a climate where there were no universities in London to offer anatomical instruction (and where surgeons held a relatively inferior standing in relation to physicians) John Hunter’s research, publications, museum of specimens and lectures are widely considered to have played an important part in surgery’s increasing emergence from the realm of craft into one of science.

Left:John Hunter. Right: William Hunter

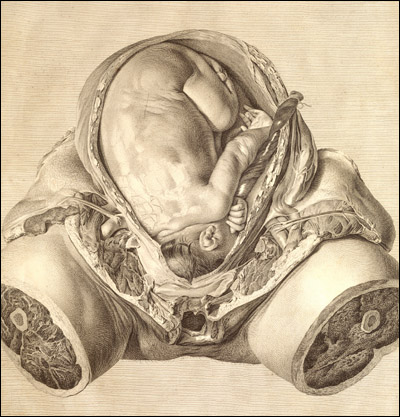

William Hunter, as well as being an anatomist and a physician, was the founder of arguably the most prominent London private medical school of the eighteenth-century - with its own anatomy lecture theatre, museum and extensive library. He has also been widely credited with the introduction in London of dissection in the ‘Paris manner’ (i.e. students having access to bodies for dissection, rather than simply observing their teacher). In addition, he was one of the most widely acclaimed man-midwives of his time, following in the footsteps of his mentors in London - William Smellie and James Douglas, both also Scots.

William Hunter, Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, 1774

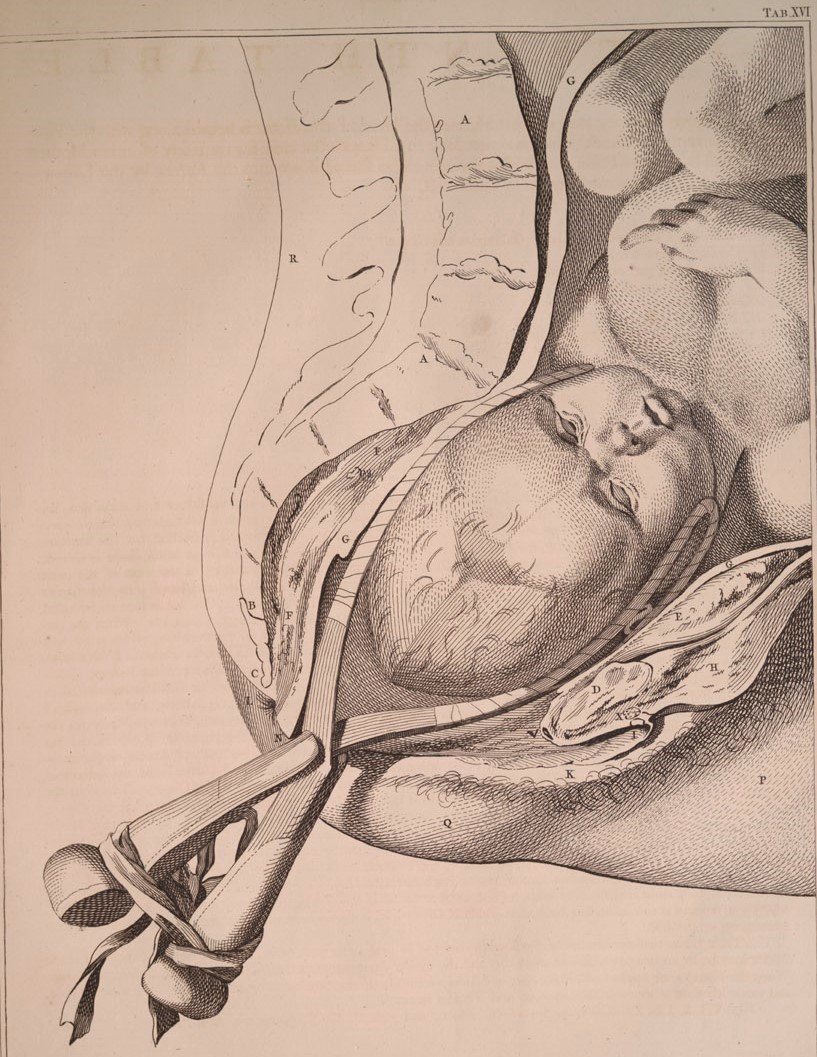

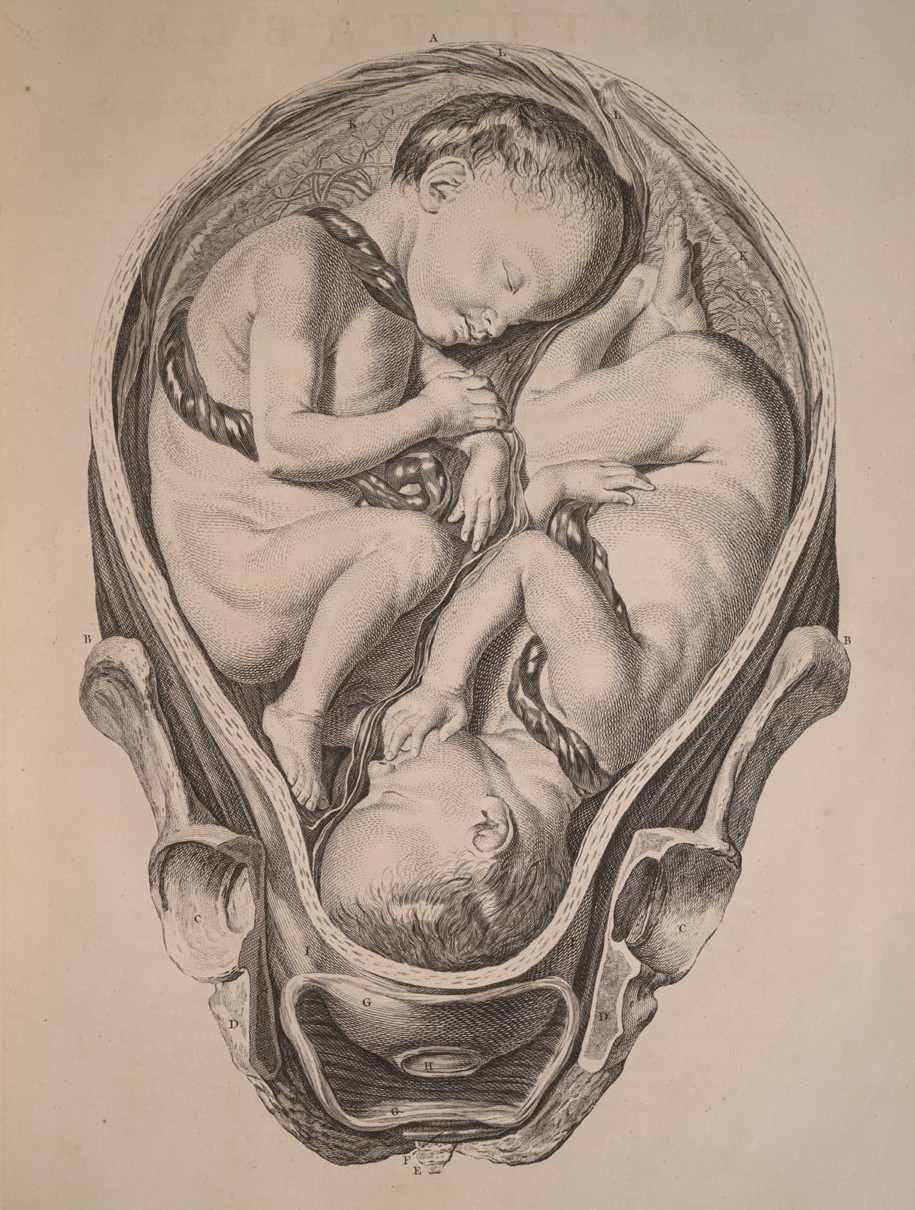

Man-midwifery

The growth of man-midwifery in London in the eighteenth-century has been considered by some as a particularly Scottish phenomenon. A range of reasons for this have been cited, such as the breadth of the Scottish medical education, their acceptance of midwifery as a subject for university education (a chair of midwifery having been established at Edinburgh in 1726) and the relative exclusion of Scots from acceptance into elite English medical circles – with this acting as an impetus in their carving of their own separate niche.

William Smellie, A Sett of Anatomical Tables, with Explanations, and an Abridgement, of the Practice of Midwifery. 1754

Pathology and therapeutics: Scottish models for understanding disease

Eighteenth-century studies on disease causation have typically been characterised by historians as a major area of Scottish contribution. Given particular prominence is the work of William Cullen, whose nosology (i.e. attempt to systematically classify disease) focussed on the central importance of nerves. This was an approach which was widely emulated, with nervous conditions becoming a central concern of eighteenth-century study.

Influences of Cullen’s work outside Scotland can be seen in London student’s lecture notes and medical diagnoses in many English infirmaries.

The uptake of his theories on contagion, particularly fever, by a number of his students who were Quakers and who then put this into practice in England’s dispensary and asylum systems is particularly significant.

Left: William Cullen. Right: John Brown

Another major figure was Cullen’s one-time pupil John Brown. Not a great deal is known about Brown (an extra-mural medical lecturer in Edinburgh). However, the influence of the nosology he established (which came to be termed Brunonianism) was widespread. The system essentially consisted of an extreme simplification of disease classification based on nerves, where the causes of disease took two forms – either over or under stimulation.

The influence of Brunonianism on the continent, particularly Germany, was great. Its uptake there by a younger generation of medical practitioners was part of a wider rejection of more traditional approaches to medicine and discord within society. The relative vagueness of Brown’s doctrine was a significant factor in its success – later Brunonians were able to add to and adapt the basic principles of his approach to suit local conditions.

Public hygiene and military service

Scots also played a significant role in military medicine in the period. The country’s physicians and surgeons were part of a particularly high influx into military-related work at this time. Explanations for this are wide-ranging, including the fact that military-related scientific subjects were taught in Scottish universities and that those who took part in military service were entitled to practice as surgeons in England without the need for the usual formal certification.

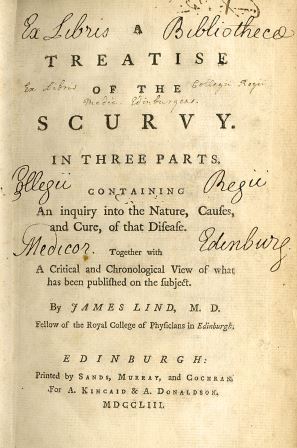

James Lind, and his writing on scurvy

A particularly studied example is James Lind (who was first a naval surgeon, then a physician). Lind carried out what is credited by some as being the world’s first controlled trial, testing various proposed cures for scurvy on a group of sailors.

If you'd like to find out more, you can email us at library@rcpe.ac.uk

To find out more about William Cullen visit The Cullen Project

To find out more about James Lind visit The James Lind Library

Follow our Twitter account @RCPEHeritage or our Facebook page or sign up to our newsletter to get notifications of new blog posts, events, videos and exhibitions.