Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

Each recipe roughly followed the same order: purpose, ingredients and how to make the medicine, then how to use it and for how long. They were written in prose, with no clear delineation between ingredients and methods. As noted in Part 1, full transcription became necessary to accurately summarise them, but each recipe had something valuable to add to the picture.

Multigenerational knowledge was preserved as new recipes were written in blank spaces or new leaves. Recipes could have come from other family members, friends, and acquaintances, or other materials, making it an inherently collaborative product. Some recipes in our book were indeed copied from printed works, such as A Rich Store-House or Treasury for the Diseased (1616) which was a compilation of home remedies. Intended as a guide for people unable to see a physician, it would not have been an unusual find in a non-medical household.

Another recipe came from a pamphlet from 1742 that described a method to prevent or cure “the present epidemical distemper” in England (in this case, an ulcerous sore throat). A recipe for the gout also came from a publication written by a man from Kilkenny in Ireland. Others might have been transmitted between individuals, since at least one recipe comes from a named person: Mr Fowler of Bilbrook, in Staffordshire. Some lists and recipes also directly reference the Directory. Thus, within one book, we can see how the exchange of knowledge between manuscript and printed sources reflect an interest in and deep engagement with scientific thought and practice.

The content of the recipes detail common physical pains and diseases that may be of concerns for a household. They address a wide range of ailments, such as various digestive issues, fevers, gout, heart problems, ulcers, worms, how to treat the bite of a mad dog, the cure for a “sleepy disease” and even a decoction against melancholy. The most common however were lung issues, coughs, and how to expel “phlegm” in the sinuses. These same issues can be found in other recipe books of the period, written by women running their household.

The ingredients used also reflect the ability of a family to access them. Indeed, there are a lot of repeating ingredients such as liquorice, aniseed, sugar candy, fennel seeds and roots, elecampane, parsley, betony, sage, and cream of tartar (potassium bitartrate, derived from grapes), but also spices such as pepper, nutmeg, cumin, cinnamon, mace, turmeric, clove, and mustard. Ingredients were often ground and boiled, and mixed with honey, milk, rose water, vinegar, broth, or ale.

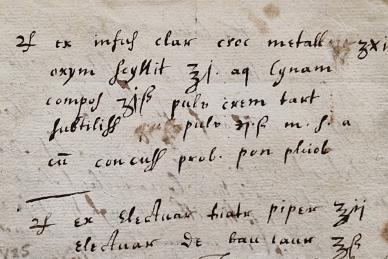

However, measurements and quantities could be carefully specified (a dram, a spoonful, an ounce), or somewhat arbitrary and vague; instructions rarely mention how long the ingredients are supposed to boil in water, for instance. The assumption was that the reader had prerequisite knowledge and some experience to be able to follow them correctly. One of the recipes is also almost entirely in Latin and heavily abbreviated, which presumes a specific kind of literacy. More commonly, the Latin phrase “probatum est” (translated as ‘it has been proved’) can be found after some recipes. This was a so-called ‘efficacy phrase’, which indicated that the writer had tried the recipe and could vouch for its success. Some recipes also include electuaries and more complex preparations, which could probably be purchased at an apothecary, or made by the author if indeed he was himself an apothecary or a student of medicine.

This is one of the recipes taken and copied word for word from another printed source, here Rich Store-House.

“A good powder to be used for the cough and wheesing of the pipes and nose

Take an ounce of Case Ginger beaten to fine powder and an ounce of Elicompanerootes dryed and beaten to powder, then take a pound of Sugar-candy beaten somewhat fine, halfe a pound of Licquorice and halfe a pound of Annis-seeds, and let them be both well searsed and then mingle all the thinges before specified together, and then put the same powder into a box or Bladder, and when you got to bed eate a spoonfull thereof and as much in the morning fasting and it will helpe you in short space

Probatum est”

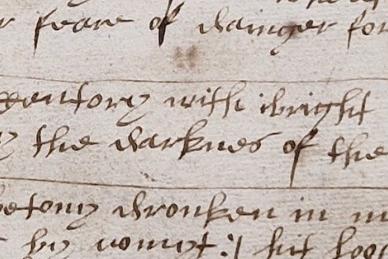

This example is quite short, but is a very common recipe. Eyebright was a prime ingredient in a lot of recipes related to eye problems. Its use, since the Middle Ages, is rooted in the medieval Doctrine of Signatures, where the appearance of a plant or herb was thought to indicate its medicinal properties.

“the iuice of canfory with ibright and hony hit purgeth a way the darknes of the eyes”

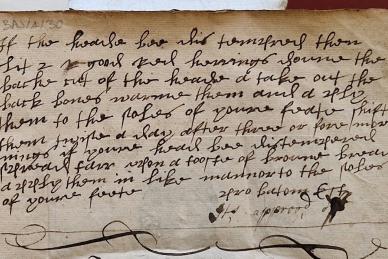

This recipe presents an interesting method of curing a ‘distemper’ of the head, by applying fish or toast to the sole of the feet. It has also been tested and approved. ‘Distemper’ originally simply referred to an unbalanced or unnatural temper, or humour, and had evolved by in the early modern period to describe a few different maladies, often infectious in nature.

“If the heade be dis tempered, then slit 2 good red herrings doune the backe cut of the heade, a take out the back bones, warme them and a ply them to the soles of youre feate, chiftinge them twice a day, after three or fore mornings if youre head bee distempered, spread tar upon a tooste of browne bread, apply them in like manner to the soles of your feete

pro batum Est

It’s approv’d off”

The catalogue for this collection can be found at DEP/BAJ/1.

Written by Declan H. A. Fourrier, who recently received their MSc in Medieval History from the University of Edinburgh.

This volume was donated to the College by Andrew Carothers in July 2024.

Bibliography and further readings about recipe books and household medicine in the Early Modern period:

Allen, Katherine. ‘Hobby and Craft: Distilling Household Medicine in Eighteenth-Century England’, Early Modern Women, vol. 11 (2016); pp. 90–114.

Criado-Peña, Miriam. ‘‘Probatum est’. The Medical Recipes in London, Wellcome Library, MS 3009’, Nordic Journal of English Studies, vol. 20 (2021); pp. 258–277.

Harvard, Lucy J. ‘Mrs Mary Chantrell (fl. 1690): Book of receipts (1690–1693)’, in Women in the History of Science, ed. by Hannah Wills, Sadie Harrison, Erika Jones, Farrah Lawrence-Mackey, Rebecca Martin (UCL Press, 2023).

Rabb, Theodore K. ‘“My Lady Sandys her receipts”: A Manuscript of Cookery and Medicine’, The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 72 (2011); pp. 454–463.

This article examines the reading notes made by Elizabeth Freke, in the late seventeenth-century, concerning Culpeper’s translation and her use of it:

Leong, Elaine. ‘Making Medicines in the Early Modern Household’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Special Issue: Women, Health, and Healing in Early Modern Europe, vol. 82 (2008); pp. 145-168.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories