Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

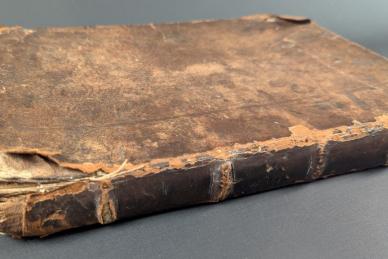

Looking at this book, no one would guess its contents.

The brown leather cover shows its age through signs of use but the spine, cracked in places, holds strong; yet the cover is bland, displaying no title, no author. By turning the cover, the mystery grows.

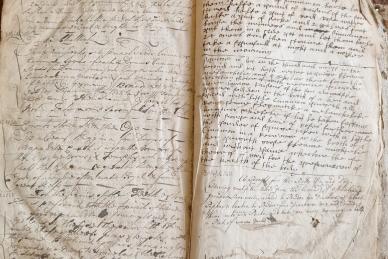

The reader is greeted by a multitude of indecipherable lines, which comes together to form nearly sixty handwritten medicinal recipes.

Leafing through them finally reveals the title page: A Physical Directory, or a Translation of the Dispensatory made by the Colledge of Physitians of London, written by Nicholas Culpeper and published in London in the mid-seventeenth century.

Culpeper was an English botanist, herbalist, physician, and astrologer. Born in October 1616, he died of tuberculosis in 1654. Ardent republican, he even fought in the civil war of 1643 and was tried (and acquitted) for witchcraft.

Trained as an apothecary, he practiced from his house in unfashionable Spitalfields, where he fully committed himself to the service of the sick among the poor, powerless, and uneducated people.

His radical goal to enable the poor to help themselves (licensed physicians were very expensive then) led him to translate and write medical books. His numerous works include the Directory for Midwives; or, A Guide for Women (1651), which made obstetrics accessible and foregrounded midwives’ professional rights.

His most famous book is The English Physician, later known as The Complete Herbal (1652) – still reprinted today. As a source of pharmaceutical and herbal lore of early modern Europe, it is reminiscent of the Physical Directory.

However, as its title page announces, the Directory is a translation. Herbalists, midwives, and other empirics could legally practice only if their services were free of charge. Apothecaries dispensed remedies prescribed by physicians, but they could also diagnose illnesses and prescribe cures, which created constant conflict with the College of Physicians of London (RCPL). To maintain its statutory monopoly of medicine in and around London, the RCPL produced the authoritative Latin Pharmacopeia Londonesis (also known as the London Dispensatory) which listed all the drugs authorised for use by physicians and apothecaries. Entirely in Latin, it was difficult to read even for some apothecaries, and impossible for the barely literate. Translating the Pharmacopeia was Culpeper’s first big project; he made it accessible in terms of readability, price, and use.

To break monopoly of physicians and apothecaries on Londoners’ access to health, Culpeper’s first edition of 1649 was later augmented with definitions of medical terms, information and warnings about the use simples and compounds, and instructions on how to pick up and conserve herbs, roots, etc, and how to make medicines. Thus, with each edition, the book became more of a complete handbook of medical self-help, as Culpeper continued to criticize the self-interest of college physicians. The RCPL later revised the Pharmacopoeia, and Culpeper also translated this version. However, the copy of the Physical Directory which we hold is only a second edition, translating the old version of the Pharmacopoeia. Printed and sold by Peter Cole ‘at his shop at the sign of the Printing-Press in Cornhil, near the Royal Exchange’ in London, the Physical Directory became popular throughout the British Isles.

As evidenced by the nearly sixty handwritten medical recipes and other miscellaneous notes, our copy was well used in its life. Handwriting styles vary, and seem to range from the mid-seventeenth century to the late eighteenth century.

It was published in London in 1650, but the rest of its history is partly unknown until Andrew Carothers donated it to us in July 2024. The book had been in his mother’s family for a long time. Her maiden name was ‘Bagnall’. Thomas Bagnall put his name in marginalia, and James Bagnall wrote his name on multiple pages, followed by the dates of 1743-4, 1745, 1739.

Sadly, we do not know have more information about the Bagnall family. Repeated signatures clearly display the book’s ownership and the importance attached to it. Another name can be found, in an earlier script: ‘John Maerewall’. This suggests changes in ownership, but it is notable that this copy was still used and referred to a century after its publication.

This copy is very similar to recipe books of the early modern period. These commonplace books, often compiled by women, who were seen as responsible for their families’ health, contained medical knowledge in the form of prescriptions, sometimes side by side with cooking recipes. They showcase the intricate relationship between ‘science’ and domestic medicine. As a multi-authored work, and even though the signatures refer only to male names, women potentially had a hand in our copy’s compilation. Since men too were instrumental in family healthcare, proffering and collecting recipes, it might be that this book was used in a household context. Indeed, not all recipes recorded are for humans (five of them concerns horses or cattle), one recipe essentially instructs to bake a cake with specific seeds and spices, and another recipe might be about making ink. Yet it is also possible that some of its owners were apothecaries or students of medicine, as usage changed over the years.

Most of the recipes are written on blank leaves, now surrounding the text block or pasted on the interiors of the front and back covers. Only one recipe was scribbled in the margin of the printed text. Other notes record various lists, bills, and maybe a grocery list with prices. There has never been an attempt at pagination or creating a table of content, so separating each recipe was difficult, and some had been unaccounted for during a previous attempt at cataloguing. Going over the recipes and titles already transcribed, then augmenting descriptions or rectifying the ingredients list where needed, provided a base for understanding the most common handwriting. This style is called Secretary Hand; it was developed in the early sixteenth century and remained common until the late seventeenth century. The other style found in the book is more closely related to the Round Hand of the eighteenth century.

Due to the lack of standardisation, ingredients within a recipe could either be at the beginning or near the end, especially if the recipe in question required two or more medicinal preparations. Transcribing every word, even if only on paper, very quickly imposed itself as an essential step before establishing an accurate ingredients list and summarising recipe contents. It seemed tedious at first, but it became faster and easier, as it helped to compare letter forms in known words to understand unknown ones. It also showed that at least two seventeenth-century hands worked on this book, and other variances may be due to different ink and pens.

Even with some experience in palaeography, reading seventeenth-century hands is tricky at best. Letter forms can be quite different from their modern equivalent, and each writer added their own flair. Comparatively, the eighteenth-century hand was easier to read, even though the recipes were often quite longer and more detailed. Spelling was also not as strict as it is today. Figuring out the ingredients took patience, as most of them had different spellings or a different name altogether. Weights and measures also required additional knowledge to grasp their meaning and abbreviations. However, Culpeper’s book revealed itself as the perfect resource. Similar to a list of every useful ingredient, the printed text becomes a reference for the modern reader to decipher the recipes. Comparing handwritten and printed elements allowed us to understand and transcribe every recipe.

In what looks like simply another example of a very popular early modern book, this copy of A Physical Directory gives insights into domestic practice, intellectual networks, and textual culture through its pages of handwritten notes and recipes. In the early modern period, printed books were understood as instrumental, as an object to engage with, and whose knowledge should be put to use. The variety of hands found here might deserve more palaeographical exploration, as their exact number is unknown. Nonetheless, the different scripts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries show the continuous engagement between this copy and its owners.

Click here to read part two of this blog.

The catalogue for this collection can be found at DEP/BAJ/1.

Written by Declan H. A. Fourrier, who recently received their MSc in Medieval History from the University of Edinburgh.

This volume was donated to the College by Andrew Carothers in July 2024.

Bibliography and further readings about Nicholas Culpeper and the history of books and reading:

Curry, Patrick. ‘Culpeper, Nicholas (1616-1654)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, vol. 14, ed. by H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford, 2004); pp. 602–605.

McCarl, Mary Rhinelander. ‘Publishing the Works of Nicholas Culpeper, Astrological Herbalist and Translator of Latin Medical Works in Seventeenth-Century London’, Canadian Bulletin of Medical History / Bulletin canadien d'histoire de la médecine, vol. 13 (1996); pp. 225–276.

Poynter, F. N. L. ‘Nicholas Culpeper and His Books’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 17 (1962); pp. 152–167.

Richards, Jennifer and Fred Schurink. ‘Introduction: The Textuality and Materiality of Reading in Early Modern England’, Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 73 (2010); pp. 345–361.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories