Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

In ancient Greece, mandrake was taken as a sleeping pill. In Medieval Europe mandrakes were carried around as good luck charms. Mandrakes were hallucinogenic and even fatal when taken in large doses. They were also associated with devil worship and witchcraft – at her trial, Joan of Arc was accused of owning mandrake.

Mandrakes were not native to Britain and so the dried roots were imported. They were in such high demand that counterfeit mandrake roots were carved from other plants.

Many myths developed around harvesting mandrake. The plant was said to shriek so loudly when it was dug up that it would kill all who heard it. One set of directions advised to tie a root of the plant to a dog and then force it to pull up the plant while you plugged your ears and hid at a safe distance. Other versions involved dancing around the plant while muttering incantations, then attaching a crucifix to it and drawing three circles around the root.

The Hortus Sanitatis (‘Garden of Health’) was the first natural history encyclopaedia. It was published in the city of Mainz, in Germany. It contains 550 illustrations of plants, land mammals, birds, fish and minerals. It is a compilation of a wide range of earlier medieval texts. The Hortus Sanitatis wasn’t constrained by what was real – it also contains descriptions of mythical creatures like the dragon, the unicorn and the phoenix.

According to the Hortus Sanitatis, the mandrake had many medicinal uses. It could be taken as a suppository or added to eye drops. When placed in the anus it was believed to operate as a sleeping pill. Mandrake roots were also boiled in wine and taken as a sedative. Although, the text warns, too much and you might never wake up.

This book is based on the work of the ancient Greek physician Dioscorides. It explores over 1,000 medicines and nearly 600 different plants. Dioscorides recommended mandrake as an anaesthetic, an enema, a snakebite antidote and a treatment for dry skin. He believed that there were two different sexes of mandrake (what we now know to be two different species). He wrote that the ‘female’ plant was especially good for making love potions.

Legends surrounded mandrakes and their use in medicine. Their popularity stemmed from what was called the doctrine of signatures. This was the idea that if a plant resembled a particular body part, it was an effective treatment for diseases of that body part. Because mandrakes resembled the entire body, they could control the entire body – including conception, love and happiness.

The author of this book, William Woodville, was an English physician and botanist. He had studied at the University of Edinburgh before setting up his medical practice in London. Woodville took up a position at a smallpox inoculation hospital in central London and established a large botanical garden close to King’s Cross station – on land which belonged to the smallpox hospital. Over the years he studied and experimented with the medicinal plants he grew there.

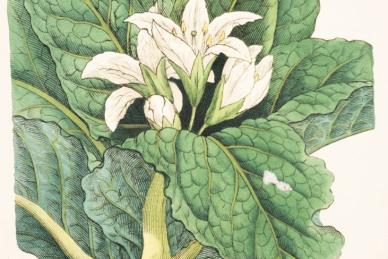

By the late 1700s, when Woodville created this text, understanding of the mandrake had significantly changed. Gone was its face, its arms, its leg-like roots. Instead, this mandrake looked much like many other flowering plants, with its human form replaced by a thick root and dark leaves.

This book is an exploration of the role of evil spirits, ghosts, the devil and mystical talismans in medicine. The book’s author, Ebenezer Sibly, was a great believer in the occult. He thought that alchemy, crystals and horoscopes could be used in the diagnosis and treatment of patients. Many of Sibly’s ideas had been commonplace in medicine 300 years earlier, but by the late 1700s – when he wrote this book – they had been discounted by everyone except for the most extreme quacks.

The image of a mandrake in Sibly’s book is similar to the images found in herbals which date from the 1400s. While other writers of his time had begun to view the mandrake in much more conventional terms, stripped of its mystical qualities, quacks like Sibly still emphasised its miraculous powers.

Support us

As a charity we rely on your donations to fund our free exhibitions, school activities and online resources