-

Quackery Online Exhibition

-

-

It can be difficult to tell the difference between what was quackery, what was folk medicine and what was just people slinging insults at each other. While in the modern day it is established that if a medical practitioner isn’t qualified, their opinion shouldn’t be trusted, the same wasn’t always true in the 1800s.

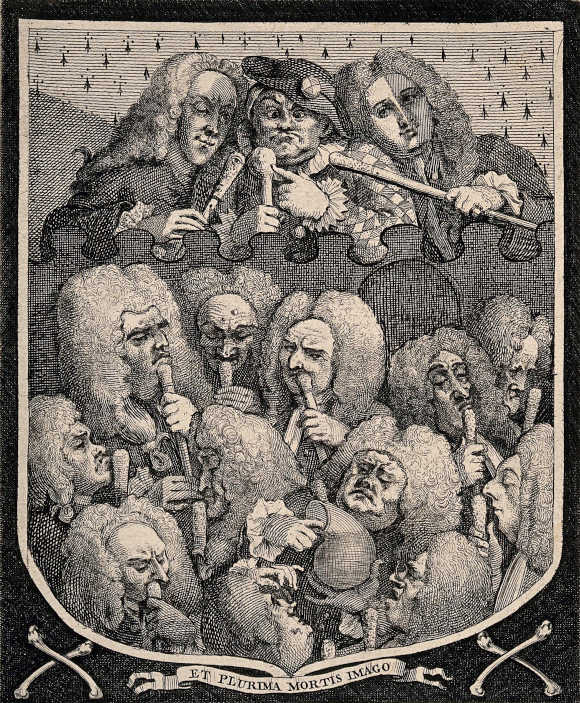

This illustration shows three quacks at the top of the shield, with a group of qualified physicians below them. The sniffing of their canes (which contained disinfectant) and their examination of a urine bottle shows how little difference there often was in the 1700s and 1800s between the methods of ‘quack’ and ‘orthodox’ medicine.

Image: The company of undertakers, William Hogarth (1736)

-

-

"Ignorance, prejudice and gullibility on the one hand – with the paucity of thoroughbred medical men on the other – opens the door to vast Imposition and quackery in these Islands"

(Alex Shand, Nesting, Shetland)

-

-

Sometimes local healers were respected for their work – with their hands-on practical learning valued by their communities. Sometimes though, however adept an unqualified practitioner was, they were judged because of their lack of a university education.

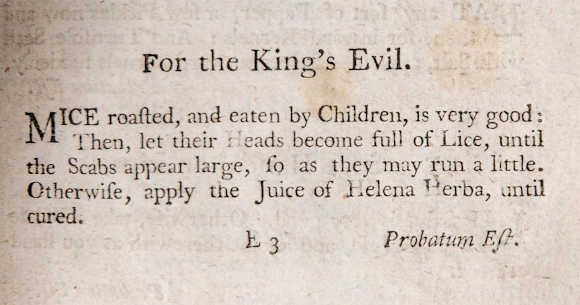

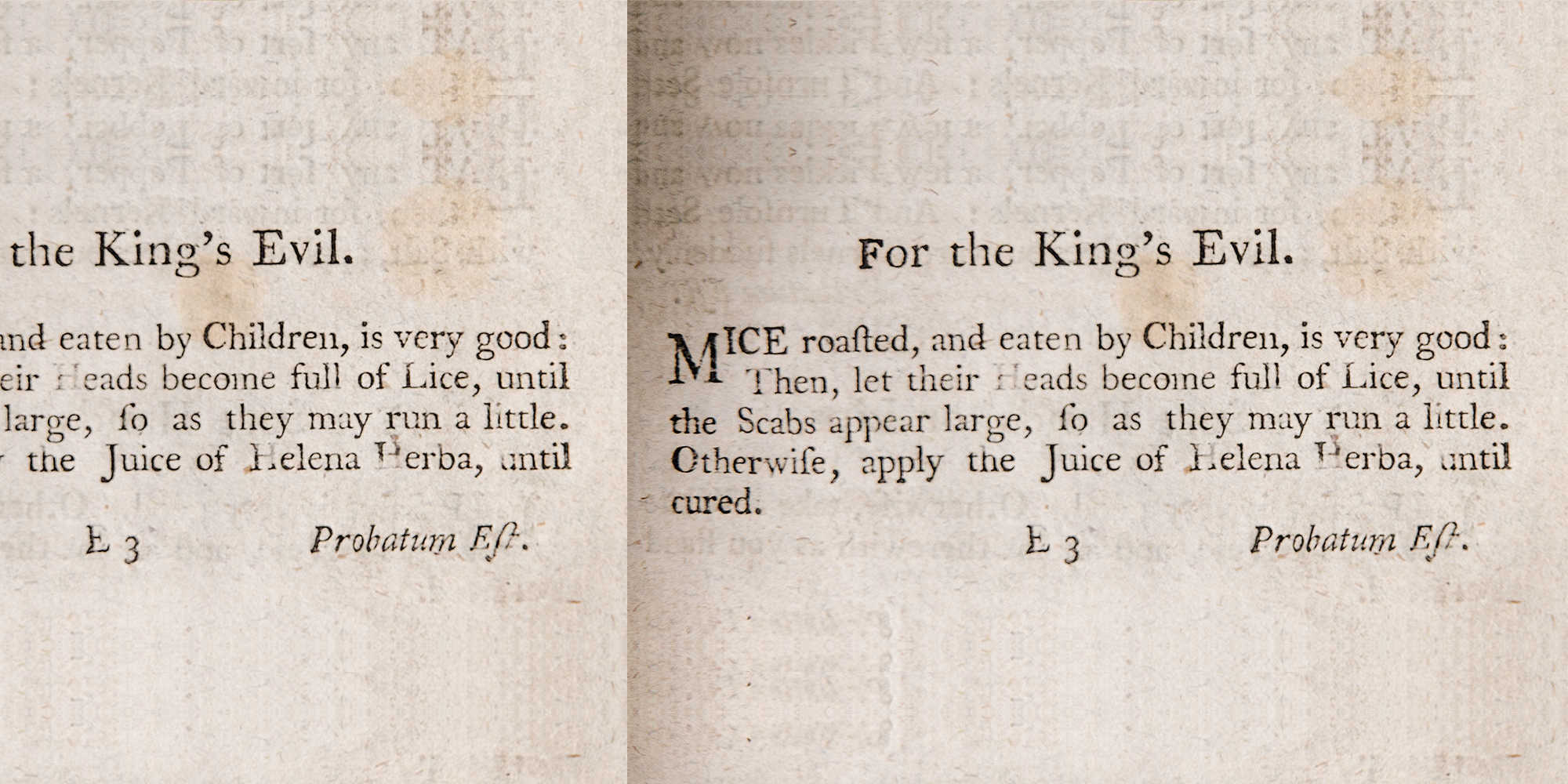

Traditional treatments, handed down from generation to generation, could be somewhat bizarre by modern standards – involving drinking urine or bat blood or eating millipedes. In this recipe, roasted mice are recommended as a cure for the King’s Evil, or scrofula.

Image: Tayler’s ready doctor, Peter Tayler (1785)

-

-

-

‘Quack’, ‘empiric’ or ‘charlatan’ could be used simply as an insult – if one qualified doctor didn’t approve of another qualified doctor’s methods he might call him a quack as a demonstration of his lack of respect.

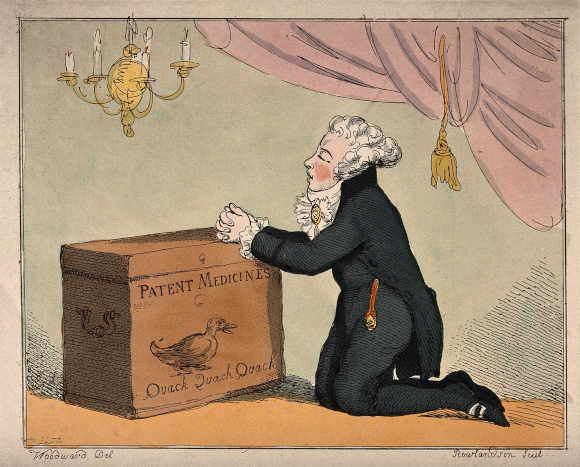

Quacks were often associated with the selling of patent medicines. From the 1700s these medicines grew in popularity – while previously you might have grown your own herbs or purchased individual ingredients, increasingly people bought pre-made mixtures. These were advertised widely in newspapers and often had outlandish names such as ‘Reanimating Solar Tincture’ and ‘Wizard Oil’. Many would claim to cure all diseases – from asthma to paralysis.

Image: A medicine vendor kneeling and praying, T. Rowlandson (1801) Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0) Image source

-

-

"During the last two years some unprincipled quacks professing to cure all diseases have fleeced the people. Their stay has been short"

(Dr Traill, Kirkwall, Orkney)

-

-

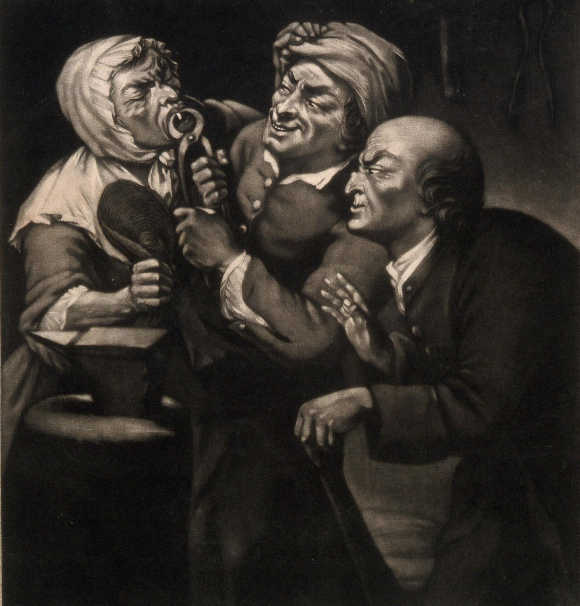

In the remote Highlands and Islands, where there were never enough qualified physicians to treat every patient, it was quite common for other respected members of the community to take up this duty. In Shetland a retired schoolmaster carried out this task. In Bonar Bridge, Islay and Tayinloan it was the resident church minister who administered medicines. In other cases ‘private families’, a church bellman and a local merchant provided medical advice to those who visited them.

Image: A rustic blacksmith turned tooth-drawer extracting a tooth, J. Wilson (c.1791) Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0) Image source

-

-

"The great body of the people entertain prejudices common to all Highlanders, against medical men they prefer the advice of Quacks to that of the first medical man in Europe"

(Donald Sage, Resolis, by Poyntzfield)

-

-

There was also a fear, however, of inexperienced and unqualified medical practitioners taking advantage of local people in the Highlands and Islands. One Lerwick-based clergyman referred to what he called ‘Ignorant Empiricy’ and in another case the local quacks were said to ‘from ignorance, do more evil than good’.

In this image Ebenezer Sibly is shown mesmerising one of his patients. Sibly gained his medical qualification at King’s College, Aberdeen. However, there is no evidence that he actually lived or studied there, ‘mail order’ medical qualifications being common at the time. To help create an air of respectability, Sibly proudly proclaimed that he was a member of the Royal College of Physicians of Aberdeen – an organisation which was unlikely to refute his claim given that it never actually existed.

Image: A key to physic, and the occult sciences, E. Sibly (1794)

-

-

-

Often the problem of quackery was blamed on the sick individual themselves. According to one clergyman in Inverness, the problem was the ‘prejudices which do generally prevail among the Highland poor against the Faculty & their partiality for quackery in every shape’. Another nearby clergyman also bemoaned that the sick poor ‘generally prefer’ to be treated by unqualified healers.

What isn’t often mentioned, when the poor are themselves blamed for their choice to go to a ‘quack’ rather than a qualified doctor, was the difference in expense. A visit to a doctor would usually cost a lot more money than a dose of castor oil from a local merchant or a bleeding from a local healer. The poor didn’t necessarily prefer quacks over qualified doctors, they often chose simply based on what they could afford.

Image: The Medical Mirror, E. Sibly (1794)

-

-

Quackery Online Exhibition

-

It can be difficult to tell the difference between what was quackery, what was folk medicine and what was just people slinging insults at each other. While in the modern day it is established that if a medical practitioner isn’t qualified, their opinion shouldn’t be trusted, the same wasn’t always true in the 1800s.

This illustration shows three quacks at the top of the shield, with a group of qualified physicians below them. The sniffing of their canes (which contained disinfectant) and their examination of a urine bottle shows how little difference there often was in the 1700s and 1800s between the methods of ‘quack’ and ‘orthodox’ medicine.

Image: The company of undertakers, William Hogarth (1736)

-

"Ignorance, prejudice and gullibility on the one hand – with the paucity of thoroughbred medical men on the other – opens the door to vast Imposition and quackery in these Islands"

(Alex Shand, Nesting, Shetland)

-

Sometimes local healers were respected for their work – with their hands-on practical learning valued by their communities. Sometimes though, however adept an unqualified practitioner was, they were judged because of their lack of a university education.

Traditional treatments, handed down from generation to generation, could be somewhat bizarre by modern standards – involving drinking urine or bat blood or eating millipedes. In this recipe, roasted mice are recommended as a cure for the King’s Evil, or scrofula.

Image: Tayler’s ready doctor, Peter Tayler (1785)

-

‘Quack’, ‘empiric’ or ‘charlatan’ could be used simply as an insult – if one qualified doctor didn’t approve of another qualified doctor’s methods he might call him a quack as a demonstration of his lack of respect.

Quacks were often associated with the selling of patent medicines. From the 1700s these medicines grew in popularity – while previously you might have grown your own herbs or purchased individual ingredients, increasingly people bought pre-made mixtures. These were advertised widely in newspapers and often had outlandish names such as ‘Reanimating Solar Tincture’ and ‘Wizard Oil’. Many would claim to cure all diseases – from asthma to paralysis.

Image: A medicine vendor kneeling and praying, T. Rowlandson (1801) Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0) Image source

-

"During the last two years some unprincipled quacks professing to cure all diseases have fleeced the people. Their stay has been short"

(Dr Traill, Kirkwall, Orkney)

-

In the remote Highlands and Islands, where there were never enough qualified physicians to treat every patient, it was quite common for other respected members of the community to take up this duty. In Shetland a retired schoolmaster carried out this task. In Bonar Bridge, Islay and Tayinloan it was the resident church minister who administered medicines. In other cases ‘private families’, a church bellman and a local merchant provided medical advice to those who visited them.

Image: A rustic blacksmith turned tooth-drawer extracting a tooth, J. Wilson (c.1791) Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0) Image source

-

"The great body of the people entertain prejudices common to all Highlanders, against medical men they prefer the advice of Quacks to that of the first medical man in Europe"

(Donald Sage, Resolis, by Poyntzfield)

-

There was also a fear, however, of inexperienced and unqualified medical practitioners taking advantage of local people in the Highlands and Islands. One Lerwick-based clergyman referred to what he called ‘Ignorant Empiricy’ and in another case the local quacks were said to ‘from ignorance, do more evil than good’.

In this image Ebenezer Sibly is shown mesmerising one of his patients. Sibly gained his medical qualification at King’s College, Aberdeen. However, there is no evidence that he actually lived or studied there, ‘mail order’ medical qualifications being common at the time. To help create an air of respectability, Sibly proudly proclaimed that he was a member of the Royal College of Physicians of Aberdeen – an organisation which was unlikely to refute his claim given that it never actually existed.

Image: A key to physic, and the occult sciences, E. Sibly (1794)

-

Often the problem of quackery was blamed on the sick individual themselves. According to one clergyman in Inverness, the problem was the ‘prejudices which do generally prevail among the Highland poor against the Faculty & their partiality for quackery in every shape’. Another nearby clergyman also bemoaned that the sick poor ‘generally prefer’ to be treated by unqualified healers.

What isn’t often mentioned, when the poor are themselves blamed for their choice to go to a ‘quack’ rather than a qualified doctor, was the difference in expense. A visit to a doctor would usually cost a lot more money than a dose of castor oil from a local merchant or a bleeding from a local healer. The poor didn’t necessarily prefer quacks over qualified doctors, they often chose simply based on what they could afford.

Image: The Medical Mirror, E. Sibly (1794)