Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

The skin held little interest for medical practitioners during antiquity and the Renaissance. When it was cut open during an autopsy, it was quickly laid aside to study the organs beneath. Anatomical works often included the skin as a visual tool – drawing it back, hanging it, flaying it – but did not study it.

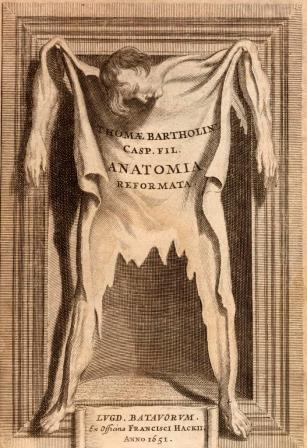

Skin was the border between the inside and the outside of the body. The frontispieces of books which showed flayed skin used it as a curtain, to be pulled aside to uncover the mysteries of the organs of the body within the text.

Treatment of the skin was often the preserve of the folk healer and the quack rather than the qualified doctor. The role of the skin as a border gave it a purpose beyond mere biology. It was a boundary between body and soul, the physical and the spiritual. According to folk belief the imagination could distort the skin, making it become hairy, scaly or change colour.

Anatomical flap sheets allowed their readers to peel back layers of skin and tissue to expose the organs and bones beneath. This text, with over 100 individual flaps, was the showiest, largest and most detailed of its time. When this illustration was originally made, around 1605, its creator Johann Remmelin was only 22 years old and still undergoing his doctoral studies in medicine at the University of Basel.

Remmelin’s work was more than an anatomical text. It contains magical, alchemical and kabbalistic elements. The female figure displayed here represents Eve, while elsewhere Adam is shown crushing a serpent underfoot. Eve’s genitals are covered here with a plume of smoke, with text directly below it reading ‘As the Phoenix lives even after it has been consumed by fire: thus man who is the likeness of smoke is also ash’.

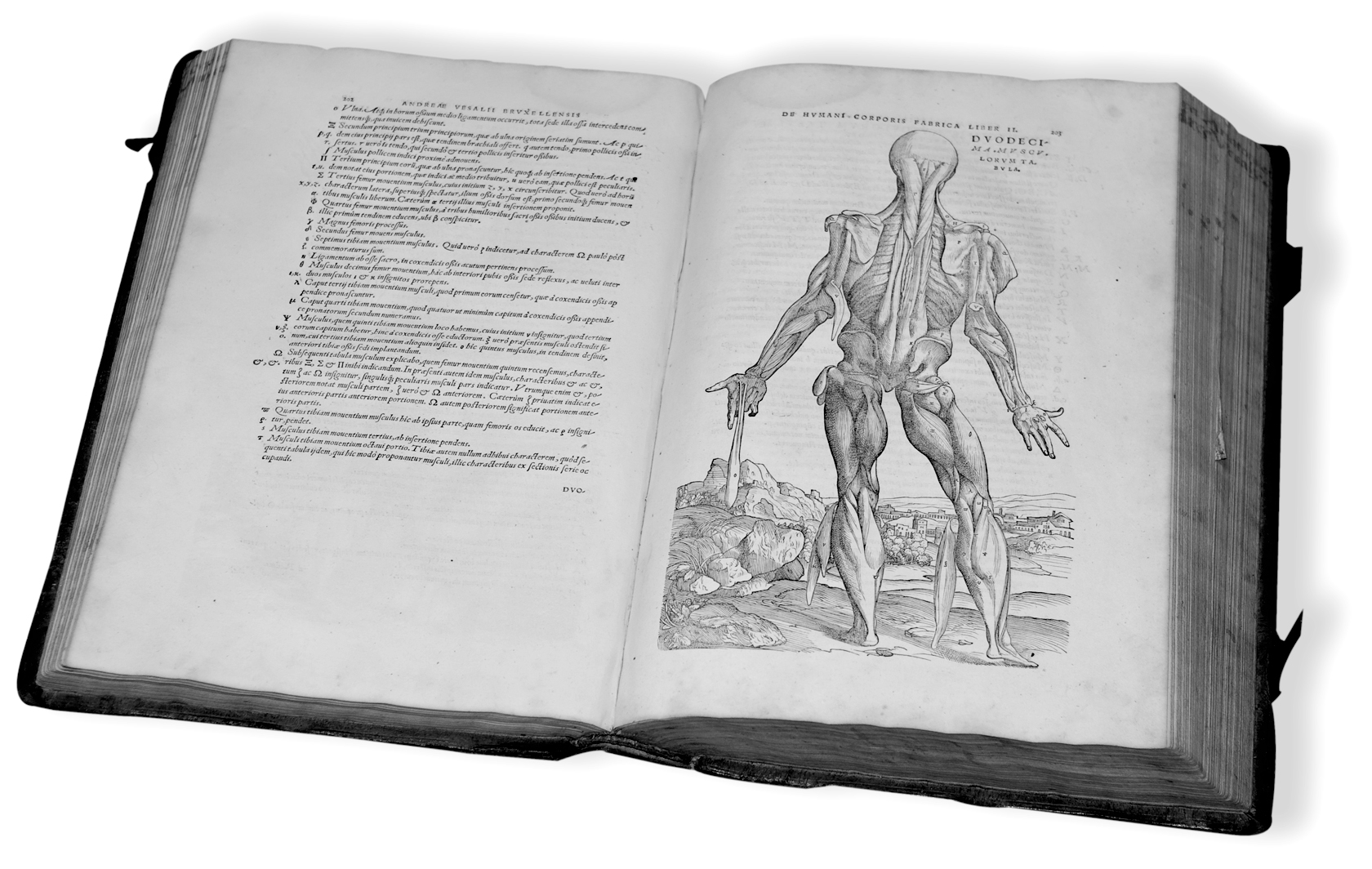

This volume was a ground-breaking work which helped set the stage for a massive effort at mapping the human body. Its author, Flemish anatomist Andreus Vesalius, was an early advocate for dissection and the importance of having first-hand knowledge of anatomy rather than an understanding which was based on reading medieval texts.

The Fabrica was translated, reissued and plagiarized over and over again in the following centuries and its illustrations were copied in other medical works until the end of the 1700s.

Although Vesalius devoted little attention in this work to the skin itself, he did record that ‘it is certain that there are two layers of skin, namely the external one, which is called the leather hide, and the interior which is the true skin and which cannot be cured if it is cut’.

In the frontispiece of this work, originally written by Danish physician Caspar Bartholin and later revised by his son Thomas, the skin is treated very casually, unevenly cut and nailed to a frame.

Flayed and tanned human skin was frequently part of university collections and was passed round to audiences at anatomical theatres to hold and examine. Anatomists navigated the cultural sensitivity around flaying by dissecting condemned criminals. Flaying, then, was just an extension of the punishment they received in life. One visitor to Leiden, in the Netherlands, recorded that they had observed a skeleton on display with ‘a shirt made of his own bowels and shoes of his own skin’.

Processes adopted to prepare human skin included boiling in water and aqua fortis, an extremely corrosive solution of nitric acid. Some anatomists also used blister beetles in its preparation.

Vesication, or blistering, was a common method of therapeutically breaching the skin that lasted well into the 1800s. An irritant, usually composed of ground up Cantharidin, also known as blister beetle or Spanish fly, was coated on a plaster which was then applied to the skin. The resulting blister was then either left to heal or continually irritated to create a constant weeping sore, known as an ‘issue’.

As well as being applied to the skin, blister beetles were also ingested - a method of treatment which could be highly dangerous, even deadly. They were believed to cure a wide range of diseases from rabies to deafness. They were also thought to have abortifacient and aphrodisiac properties and the French writer the Marquis de Sade was alleged to have poisoned two women after feeding them Cantharidin-laced sweetmeats as a sexual stimulant.

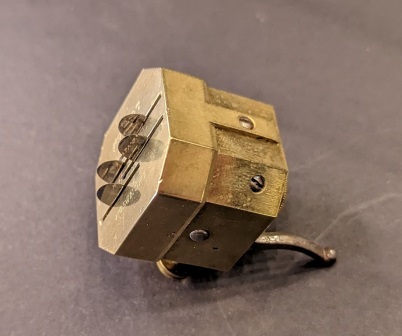

Scarificators were first developed in the early 1700s, although they reached the peak of their use in the 1800s. They have spring-loaded blades that deliver many cuts simultaneously. The depth of the cuts can be changed by altering the spring mechanism.

Therapeutic bloodletting remained a standard form of treatment into the 1800s and, due to popular demand, leeches were increasingly expensive and difficult to come by. The cultivation of leeches by leech farmers became a thriving industry. Scarificators were developed as a form of ‘artificial leech’. The anticoagulant effect of a live leech bite often made it difficult to stop the bleeding. It was also impossible to be sure exactly how much blood was removed when using leeches. The scarificator also had the advantage of being easy to transport and have on hand whenever the physician or surgeon required it.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Skin: A Layered History, which ran from 10 February 2023 to 13 October 2023.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories