Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Hooked: 500 Years of Addiction (30 May 2025 - 13 February 2026).

Addiction arrived in waves. At first doctors prescribed alcohol and opium to their patients. In the early 1800s, when the dangers of pure opium became too obvious to ignore, doctors started to replace it with a new wonder-drug. This drug was morphine – an opium derivative. When morphine itself proved addictive, doctors began to substitute another opioid – heroin.

The cycles of addiction continued. Cocaine was administered to treat alcoholism, tobacco habits and opium addiction. In the early 1900s, when the risk of administering cocaine became clear, it was increasingly replaced with newly developed synthetic amphetamines.

In 1853 Alexander Wood, a past President of our College, revolutionised medicine. Wood invented the first hypodermic syringe, a tool which was vital for administering standardised doses of medicines and safely delivering vaccines. It also changed the face of addiction forever. Before this invention, opiates had been taken in liquid form. The strength of dose, the risk and the rates of addiction all vastly increased when opiates began to be taken intravenously.

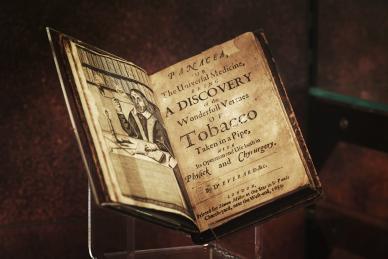

In the years after tobacco was first introduced into Europe it was lauded as a panacea – a remedy for every possible dis ease. In this book the Dutch physician Giles Everard collected together dozens of the supposed medicinal uses for tobacco. According to Everard, and others, tobacco could prevent plague and cure flatulence, asthma, syphilis and even cancer. It could be used to glue together fresh wounds and clean infected sores. It could be medicinally smoked, chewed, drunk, applied as an ointment or taken as an enema.

Two hundred years later, tobacco enemas continued to be recommended by doctors for a whole range of conditions, including constipation, tetanus and intestinal worms. In the 1920s salves made from tobacco leaves were still being recommended for ulcers and athlete’s foot.

Addiction has long been connected with mental illness. Victorian psychiatrists spoke of ‘tea mania’ which caused hysteria, nightmares and suicidal impulses.

Alcohol, tobacco and opium were all viewed both as potential causes, and as possible treatments, of mental illness.

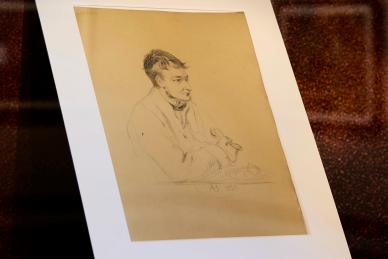

This illustration shows Mr Steerman, a tailor who was a patient at the Hanwell Asylum in London. He was 40 years old when he was admitted to the asylum and at that point, according to his doctor’s notes, Steerman had already been ‘ten years insane’. His mental illness was attributed to his heavy drinking and his condition was extreme – he began to suffer from catalepsy and would stand trance-like for hours. The treatments he was given in the asylum were harsh, including vomits, electricity, enemas and blistering of the skin.

These two opium-based medicines were manufactured by the Edinburgh company, Duncan, Flockhart & Co. They are similar drugs – laudanum was scientifically known as tincture of opium and paregoric was known as camphorated tincture of opium. As laudanum was often twenty-five times stronger than paregoric, any mix-up between them in a prescription could prove fatal. This was particularly concerning as paregoric was a treatment typically given to young children to relieve teething pain, control diarrhoea and send them to sleep.

Other opium-based medicines marketed as products for children included Mother Bailey’s Quieting Syrup and Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup. Victorian attitudes to opium use were complex – when it was taken by the working classes it was a dangerous addiction, but when the middle or upper classes took it, it was merely a habit.

This bag promotes Vicodin, an opioid. It was made to be gifted by a pharmaceutical sales representative to a physician. It dates from the early days of the opioid crisis in the United States, when the country experienced a sharp rise in the misuse of prescription drugs.

The crisis began in the mid-1990s with the release of OxyContin. The company behind this opioid marketed their product in new and relentless ways. They funded research, paid doctors to market their product and employed over 1,000 drug representatives to visit physicians across the country. Other opioid manufacturers followed their lead. They produced branded cuddly toys, fishing hats and pens. Opioids were marketed as pain-relief medicine, not just for post-surgery or palliative care, but for minor long-term aches and pains as well.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories