Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Hooked: 500 Years of Addiction (30 May 2025 - 13 February 2026).

What we mean by addiction is ever changing. In 1600s Britain, reading books was seen as addictive. You could also be addicted to astrology or to writing poetry. In the 1700s many doctors were concerned about the addictive properties of coffee and tea, while opium and cocaine could be bought over the counter without a prescription.

The terms ‘addict’ and ‘alcoholic’ weren’t used to describe heavy drinkers until the late 1800s. But, in the meantime, there were plenty of other terms which served the same purpose – including dipsomania, delirium tremens and alcohol insanity. You might not have been diagnosed with alcoholism, but you could be an ‘inebriate’, a ‘drunkard’ or the victim of your ‘habit’ or ‘vice’. Instead of an opium addict, you were an ‘opium eater’ or an ‘opiumate’.

Nowadays we view addiction as absolute – you are either addicted, or you are not. In the past there was a much larger grey area and people were viewed as a bit addicted, partially addicted or mostly addicted.

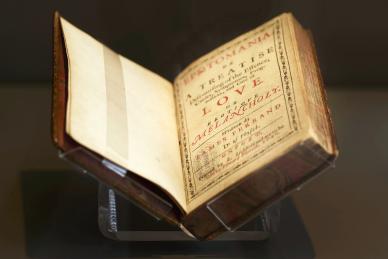

This book, by French physician Jacques Ferrand, explores the addictive nature of unrequited love. Nowadays, the word ‘addiction’ is often taken to mean ‘substance dependence’. Alcohol, nicotine and opiates are generally agreed to be addictive substances. Whether behaviours can be addictive is more contentious – only gambling is officially recognised as a behavioural addiction.

When doctors wrote about addiction 400 years ago, it was much more common to talk about behaviours being addictive. Reading could be addictive and so could praying. You could be addicted to jealousy, to melancholy and to love. According to Ferrand, symptoms of love addiction included a swollen face, sighing and constant tears. Thankfully, there were treatments at hand. These included eating lettuce and pears, and avoiding ‘hot, provocative, flatulent and melancholy meats'.

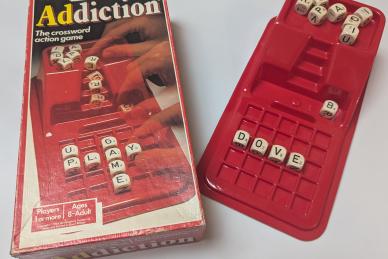

This board game was manufactured by Waddingtons, a Leeds-based company who are responsible for dozens of popular games, including Boggle and Cluedo. Addiction is a word puzzle – a variation on the Scrabble format.

This game is one of a large range of products which show how the word ‘addiction’ began to enter everyday language during the second half of the 20th century. Toys, books, mugs and clothing were all emblazoned with the word ‘addict’. On the internet, accessories can be found emblazoned with ‘sneaker addict’, ‘addicted to unicorns’ and ‘I am a wax-melt addict’.

In a more medical context, specialists continue to debate whether behaviours such as shopping, exercise, eating, playing video games and sex should be seen as potentially addictive.

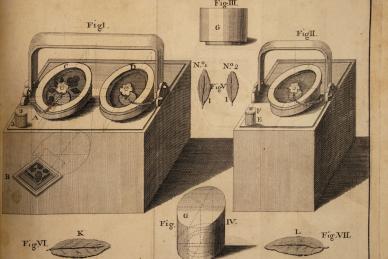

Scottish botanical artist Elizabeth Blackwell created this herbal to act as a practical guide for physicians and apothecaries. She described the coffee plant, illustrated here, as good for those who had a naturally cold disposition, but for those who ran hot, drinking too much could ‘bring on them nervous distempers’. Even before caffeine was discovered in the 1800s, coffee was thought of as an addictive and psychoactive substance. Its critics argued that it could cause impotence, paralysis and death.

Coffee was also seen as subversive. The first British coffee house opened in Oxford in 1650. Similar establishments soon began to appear in all major British cities. Men met in these coffee houses to discuss politics, philosophy and court gossip. They became known as ‘penny universities’, as the coffee typically cost a penny a cup.

Georgian Britain was awash with tea. The literary giant Samuel Johnson was a self-confessed ‘shameless tea-drinker’ whose ‘kettle has scarcely time to cool’ between cups. Tea smuggling at this time was common and at its peak millions of pounds of tea were illicitly carried into Britain every year. Tea was in such high demand it was often counterfeited – with concoctions made of local plants mixed with turpentine, paint and sheep dung. This book, by a Danish physician, shows an authentic Chinese tea leaf (bottom left) in comparison with ‘spurious’ substitute leaves.

Tea was first imported into Europe from China by the Dutch East India Company in 1610. Elsewhere in Europe interest in tea declined during the 1700s, mostly replaced by coffee. Britain’s increasing control over the tea trade meant they had easier access to cheap imports.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories