Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

This blog was developed to accompany the exhibition Hooked: 500 Years of Addiction (30 May 2025 - 13 February 2026).

Addiction is interwoven with colonialism. Enslaved people in the United States produced the tobacco, sugar and coffee which enabled European habits. Across Asia, the British East India Company was given unprecedented powers by the British government to force their will on entire nations – including the right to print money, run private armies and even declare war.

The East India Company controlled complex networks of trade – forcing mass opium production in India, which was then illegally imported into China in exchange for tea. When Chinese authorities attempted to stop this smuggling, the British government declared war. After twenty years of intermittent conflict, known as the Opium Wars, China was forced to officially open its ports to British trade. To prevent China holding a monopoly on tea production, the British then established tea plantations in India. Control of the international opium and tea trades ensured that Britain had ready access to both substances at low prices.

The English physician John Jones compiled this table to explain the safe doses of 15 of the most popular opiates. He separated them into ‘strong’, ‘middling’ and ‘weak’. Doses were not based on the physical size of patients, but on what Jones called their ‘texture’. People who were viewed as ‘soft’ or ‘fine’ should be given smaller doses than those who were ‘hard’ or ‘rough’.

In the right dose, according to Jones, opium could cure measles, plague and asthma. In 1700, when Jones compiled this book, the Opium Wars and the subjugation of China by Britain was still to come. The opium found for sale in Britain had been brought there by the Dutch. The hypodermic syringe had not yet been invented and opium was usually taken in liquid or pill form.

Tobacco arrived in China in the 1600s and a smoking culture quickly developed. Smokers soon started to mix their tobacco with opium. Over time, opium began to be smoked on its own. Chinese opium pipes, like this one, were usually made of bamboo. They could also be made of materials like silver or jade, but bamboo was preferred because its absorbent nature meant it was ‘seasoned’ by the opium over time.

Opium smoking became part of a Western caricature of Chinese people. Smoking parlours were renamed as opium dens. Racial tension was stoked by rumours that these parlours were places where white women would be abducted and forced into prostitution. In Britain, in 1914 new legislation declared that smoking opium was proof of ‘moral depravity’. This allowed for the deportation of members of the Chinese community.

Georgian Britain was awash with tea. The literary giant Samuel Johnson was a self-confessed ‘shameless tea-drinker’ whose ‘kettle has scarcely time to cool’ between cups. Tea smuggling at this time was common and at its peak millions of pounds of tea were illicitly carried into Britain every year. Tea was in such high demand it was often counterfeited – with concoctions made of local plants mixed with turpentine, paint and sheep dung. This book, by a Danish physician, shows an authentic Chinese tea leaf (bottom left) in comparison with ‘spurious’ substitute leaves.

Tea was first imported into Europe from China by the Dutch East India Company in 1610. Elsewhere in Europe interest in tea declined during the 1700s, mostly replaced by coffee. Britain’s increasing control over the tea trade meant they had easier access to cheap imports.

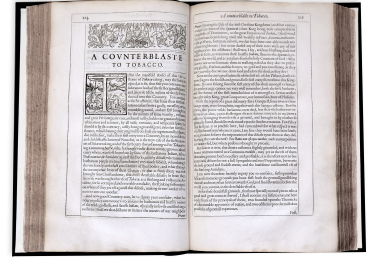

This book was first published in 1604, only a year after its author was crowned king of England. It was intended as a strong message against what James called ‘this vile custome’ of smoking the ‘noxious weed’. Although strongly anti-tobacco, James did not argue that it should be outlawed. Instead, he introduced a 4,000% tax increase on tobacco products.

James was concerned with the political and the health implications of tobacco. In the early 1600s tobacco was only grown in regions of the Americas which were controlled by Spain. Once tobacco began to be produced in British-controlled Virginia in 1612, James’s stance towards the plant softened. It now offered him a significant source of revenue and James nationalised the British tobacco trade, with all income going directly into his coffers.

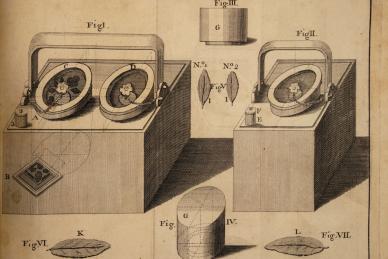

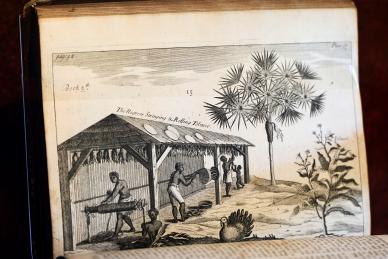

This book shows the role of the slave trade in fuelling Europe’s addictions. Its author, Pierre Pomet, was King Louis XIV’s chief druggist. Pomet compiled this text as a summary of all plant, animal and mineral products which were considered to be drugs.

It demonstrates the production methods of sugar, coffee and, in this image, tobacco. The enslaved people in this illustration are shown stripping, drying and rolling tobacco.

The desire of Europeans for these addictive substances, and the desire of their rulers to make a huge profit, fuelled a shift in the countries they colonised from white indentured servitude to an enslaved labour force. Demand for addictive substances, whether opium, tea, coffee, tobacco or sugar, fuelled the colonial expansion of the European empires.

This anonymously-written book-length poem explores the dangers of snuff-taking. The practice of snuffing - snorting a powdered mixture of tobacco leaf and stalk - was brought to Europe by the Spanish after their colonisation of Central and South America.

Once snuffing reached Europe the process became increasingly extravagant and ceremonial. Leaves were steeped in flavoured oils, held in jewelled snuffboxes and taken using tiny spoons made from gold or silver. Snuffing was a sign of social status - the elite snorted their tobacco, while the less wealthy smoked theirs. Over time, as snuff began to be produced locally in Britain, prices dropped and it also became available to the less well off. By the 1800s snuff was everywhere and sales far outstripped those for pipe tobacco.

This pipe was made in a factory in the East End of Glasgow. The manufacturer was a small company, named after its owner Thomas McLachlan. By the time that the McLachlan company was in business, Glasgow had been a commercial hub for over 200 years.

Slave-produced colonial goods were amongst the main items of trade in the city, including ginger and cotton and, most of all, sugar and tobacco. Along with tobacco came other related trades – snuff production, tobacco spinning and clay pipe production. Pipes from Glasgow were sold all over the world, with a strong market in North America. Mass produced rolled cigarettes only began to be manufactured in the 1880s and only rose to prominence in the First World War. Until that time, pipe smoking remained the primary way of consuming tobacco.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories