Physicians' Gallery Newsletter

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories

Empowering medical excellence, shaping healthcare futures.

In the latter part of the eighteenth century Anton Mesmer claimed to have discovered a 'universal fluid' manipulation which could be used to treat almost all diseases. He called this 'fluid' Animal Magnetism.

He brought his discovery to Paris where it divided the medical community, the majority of whom regarded Mesmer as a charlatan and his treatment as a sham though a few doctors were persuaded by Mesmer's results. In complete contrast, the public generally welcomed Mesmer and there was a huge demand for his treatments.

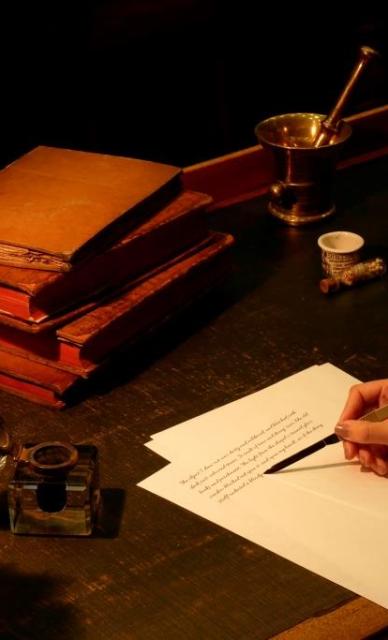

Contemporary print showing treatment by Mesmer’s Animal Magnetism. The patients seated round the bacquet, a wooden tank filled with bottles of ‘magnetised water’, hold iron cranks reaching into the bacquet against the affected parts. A woman on the left is being magnetised by a standing operator: she may possibly be undergoing a crise.

Image courtesy of Wellcome Images

Mesmer's theory of Animal Magnetism and his claims of success in using Animal Magnetism to treat patients with a wide variety of diseases raised heated public controversy in pre-revolutionary France and much anxiety among medical practitioners.

Contrary to popular belief, however, Mesmer did not, in fact, practise the techniques of hypnosis which were later associated with his name (Mesmerism), though it was probably during experiments with Animal Magnetism that these were discovered, or at least came to public attention.

In 1780 Mesmer approached the Faculté de Médecine in Paris asking it to supervise a trial of the results of his treatment of patients using Animal Magnetism. He insisted that such a trial should be only of the results of his treatment whose details he would not disclose. His proposals involved two groups of twelve patients, who were to be assigned to a group by 'the method of lots', one group to be treated by conventional methods the other by Animal Magnetism. Venereal diseases were to be excluded otherwise he made no conditions about which disorders could be included.

The trial was to be overseen by the government but the arrangements were to be made by the Faculté. The Faculté rejected the proposals out of hand and condemned one of their members, Deslon, who had presented the petition on Mesmer's behalf.

The Faculté's dismissal of Mesmer's proposals without any consideration at all caused some public criticism and, eventually, Mesmer approached the Queen, Marie Antoinette.

In 1784 Mesmer's claims were investigated by a number of official bodies, most notably by a board of Commissioners set up by order of Louis XVI and his government and by a panel of investigators from the French Royal Society of Medicine. Of these reports much the most important is that by the Royal Commissioners who included Benjamin Franklin and Antoine Lavoisier as well as the then famous astronomer Jean-Sylvain Bailly.

Their account of the investigation of Animal Magnetism contains some of the earliest descriptions of blind trials and is a model of clarity of thought and careful experimentation.

You can read the report in full, along with other contemporary documents, under this link.

Lavoisier's unpublished writings on Animal Magnetism (Paris, 1865), with a page-by-page translation, can be found here.

Author: IML Donaldson, Honorary Librarian RCPE, Emeritus Professor University of Edinburgh.

Updates on upcoming events, exhibitions and online stories