Introduction

Being a junior doctor is a demanding role and the risk of low morale, fatigue and burnout are increasingly recognised.1,2

The causes of low morale are complex and relate to several factors,2,3 which have impacted upon junior doctors working experiences over recent years.

The role of a junior doctor has become increasingly challenging, and the loss of the traditional medical ‘firm’ structure has contributed to a sense of disengagement and loss of team culture.1 More recently, the introduction of a new Junior Doctor Contract led to unprecedented junior doctors strikes, further impacting morale.

There are concerns that low morale is impacting upon junior doctors’ future career choices and retention within the medical workforce.4 The number of doctors taking a ‘break’ from training after completing the Foundation Programme increased from 30% in 2012 to 57.4% in 2017.5 The drivers behind these changes are complex and may reflect a desire for more flexibility in training, opportunity to travel or work abroad, or to focus on personal health and wellbeing.6

In order to meet the needs of the future National Health Service (NHS) medical workforce, greater emphasis needs to be placed upon improving the working lives of junior doctors and to continue to make a clinical career attractive in the UK.7,8

In this study, we aimed to identify and explore the factors affecting junior doctor morale in a large UK teaching hospital.

Methods

The study was conducted between November and December 2017 in a large three-site UK teaching hospital with 943 junior doctors.

Discussions took place with stakeholders, including senior educators, junior doctors, senior clinicians and medical education managers, to inform the development of an online questionnaire.

The questionnaire (Appendix 1) was designed to capture a comprehensive picture of junior doctor morale in domains aligned to a recent report.3 Respondents rated their overall morale and how valued, supported and autonomous they felt at work using an ordinal Likert scale of 0 (low)–10 (high). A number of validated relevant questions from NHS Staff Survey were incorporated into the survey. In addition, respondents selected the top five factors that positively affected their morale, from a pre-populated list of 20 factors that was formulated by the authors and local stakeholders.

Respondents were invited to give free-text comments and suggestions to improve morale.

All junior doctors employed in training or nontraining posts, and of all grades were invited to participate. The questionnaire was distributed by email containing individualised links, using an online software survey package, KeySurvey (KeySurvey, UK). Periodic automatic reminders were sent. All responses were anonymous.

Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS 24.0 Statistics (IBM, USA) and further analysis performed using nonparametric independent sampling and correlation analyses with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad, USA).

Free-text comments were thematically analysed to generate themes by two authors (RS and JK) using a grounded theory approach.

Approvals

The project was approved by the hospital as a service improvement project (reference number: 9797).

Results

A total of 402 (42.6%) junior doctors responded to the survey. Of these, 325 identified themselves as being in a training post, 63 in a locally employed doctor/nontraining post and 14 as unclassified.

There were 141 foundation doctors, 82 core-level doctors and 176 specialty trainees from a range of specialties. Three doctors identified themselves as ‘other’ and were included for analyses relating to overall trends, but were excluded from analyses comparing foundation, core-level and specialty-level doctors.

Respondents had worked in the Trust for <1 year (n = 184), 1–2 years (n = 108), 2–4 years (n = 64), >4 years (n = 46).

Quantitative results

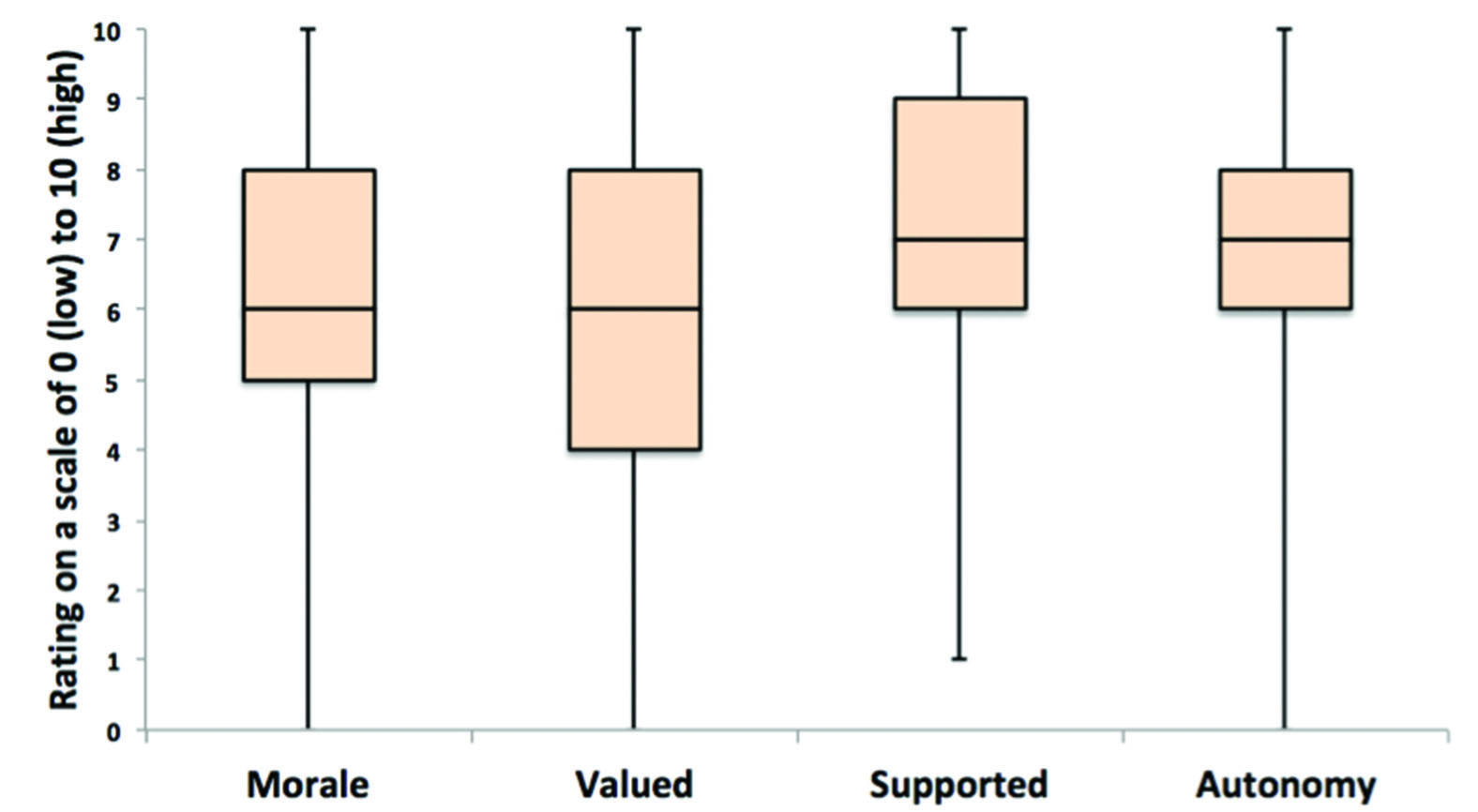

The median self-rating was: overall morale 6 [interquartile range (IQR): 5–8], feeling valued 6 (IQR: 4–8), supported 7 (IQR: 6–9) and autonomous 7 (IQR: 6–8). When comparing the four domains of feeling supported, feeling valued, having autonomy and overall morale, respondents felt most supported overall (n = 402, χ2 = 85.6, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Junior doctor self-ratings of overall morale, and the themes of how valued, supported and autonomous they felt

Doctors who felt better supported at work also felt more valued (r = 0.617, p < 0.0001), and indicated that they felt they had more autonomy at work (r = 0.591, p < 0.0001). Those who expressed higher autonomy felt more valued (r = 0.609, p < 0.0001).

Specialty trainees felt most supported (n = 176, χ2 = 7.2, p = 0.03).

Those who worked in the hospital for longer than 4 years felt most autonomous (n = 46, χ2 = 10.9, p = 0.01).

Selection of ‘top five’ factors

Junior doctors selected ‘feeling part of a team’ (66.4%) and ‘being recognised for good practice’ (56.7%) as the top factors impacting positively on their morale (Table 1).

Table 1 Factors reported as having a positive impact on junior doctors’ morale, shown in order of frequency of selection (%*) within respondents ‘top five’ choices

| | |

1 | Feeling part of a team | 66.4 |

2 | Being recognised for good practice | 56.7 |

3 | Being able to take regular breaks | 37.3 |

4 | Ease of opportunity to take leave for personal life and events | 33.6 |

5 | Having access to a computer or workstation | 31.8 |

6 | Having protected teaching time | 31.6 |

7 | Having someone to go to when a problem arises | 30.6 |

8 | Ease of sick/annual/study leave process(es) | 28.1 |

9 | Having input into my rota | 25.6 |

10 | Time for structured feedback from consultants | 22.1 |

11 | Ability to give feedback when I am concerned about a clinical issue | 19.2 |

12 | Opportunities to go to clinics or other learning events | 18.7 |

13 | Opportunities for flexible working | 17.9 |

14 | Somewhere to store my belongings securely | 17.7 |

15 | Having access to hot food and drinks | 16.7 |

16 | Being able to give positive feedback or praise a colleague | 14.9 |

17 | Opportunities to teach peers or medical students | 11.2 |

18 | Having a well-functioning doctor’s mess | 6.2 |

19 | Ability to give feedback about nonclinical issues that concern me | 6.0 |

20 | Opportunities for nonclinical working e.g. QIPs | 5.2 |

21 | Other | 2.5 |

Analysis of free-text comments

A total of 511 free-text comments were received in response to being asked what made junior doctors feel more or less valued, supported or autonomous. A total of 217 free-text comments were received in response to being asked how morale could be improved.

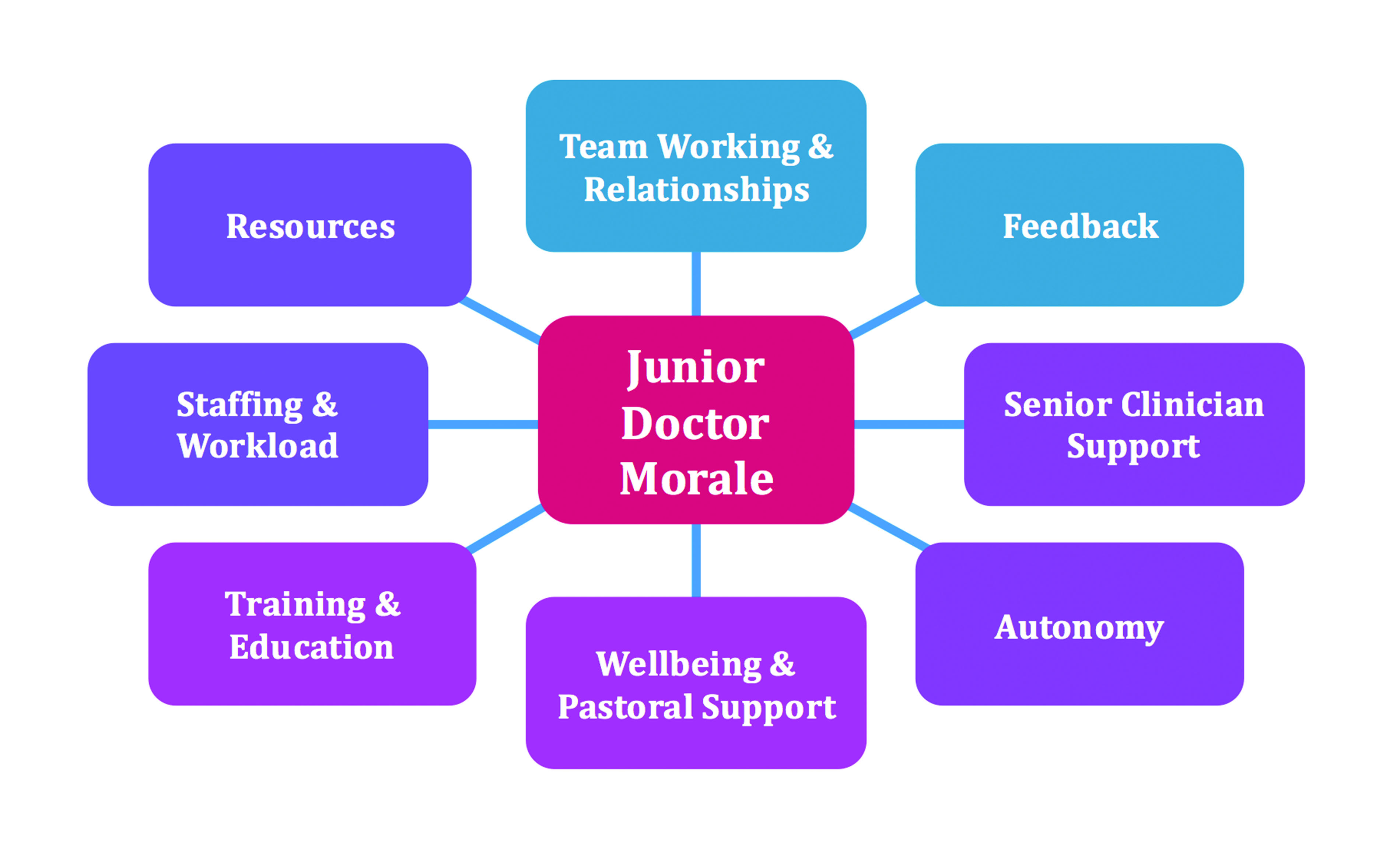

Open coding was used to sort this data initially, which was then selectively coded to produce ‘detailed themes’ (Table 2). These were subsequently selectively coded and distilled into ‘key themes’ (Figure 2).

Table 2 ‘Detailed themes’ produced by thematic analysis of free-text comments*, using grounded theory

| |

Feedback - Rewarding good work and acknowledgment of their effort

- Feedback from consultants and the multidisciplinary team

- Feedback from patients and their families

Team working and relationships - Sense of belonging to a team

- Good communication with clinical and nonclinical colleagues

Training and education - Training opportunities and career development

- Good induction to new rotations

- Food availability at organised teaching sessions

Wellbeing - Pastoral support from consultants and nonclinicians

- Recreational activities, e.g. hospital football

- Ensuring adequate and timely breaks

- Smooth administrative process to obtain leave

Job satisfaction - Manageable workload

- Having appropriate level of autonomy

- Overall job satisfaction

| Team working and relationships - Poor communication with clinical team, and nonclinical colleagues, e.g. managers

- Poor communication between departments, e.g. when making a referral

- Bullying/undermining/lack of respect

Workload - Lack of adequate medical staffing

- High rota intensity and rota gaps

- Working above the rostered hours of work and difficulties in exception reporting

- Being given inappropriate tasks

- Excessive overall workload

Resources - Lack of food and drink out of hours

- Lack of office space

- Difficulty obtaining car parking

- Complex IT systems

- Lack of rest areas, particularly when on-call

- Poor standard of doctor’s mess

Feedback - Lack of positive feedback and feeling unappreciated

- Service provision being prioritised over training opportunities

- Inability to attend lunchtime teaching owing to workload

- Payroll difficulties

|

| |

Availability of support from senior clinicians (consultant and registrar) - Good access to senior doctors

- Senior clinical cover readily available

- Approachable seniors

- Pastoral support

Availability of support from other groups Groups where support was available included: - Multidisciplinary team

- Inter-departmental

- Nonclinical, e.g. managers, junior doctor administrators

- Junior peers

Training and education - Senior guidance and supervision

- On-the-job training opportunities

- Nonclinical opportunities, e.g. audit and quality improvement

| Lower level of senior clinician (consultant and registrar) support - Occasions when there is poor access to seniors

- Lack of senior cover

- Occasions when seniors were unapproachable

Lower level of support from other groups - Lack of support from members of the multidisciplinary team

- Receiving inappropriate referrals from other specialties, or challenges when making referrals

Training and education - Lack of time for nonclinical tasks Inadequate induction

- Rota gaps and staffing issues, resulting in impact on workload, and thus opportunities for training

- Difficulty taking leave

Level of responsibility - Some trainees felt they had too much responsibility without adequate senior support

- Some trainees felt they were oversupervised and lacked sufficient independence to develop practice

|

| |

Responsibility for clinical decision-making - On the wards

- On-call

- Other settings, e.g. clinics, theatre

Being supported and receiving feedback for clinical decision-making Independent working | Lack of appropriate responsibility for clinical decision-making - Too much senior input, reducing autonomy to make decisions

- Overburdening of proformas and tick-box approach

- Clinical complexity

|

Figure 2 ‘Key themes’ affecting junior doctor morale, identified from analysis of free-text comments.

Discussion

The results of this survey provide an analysis of the key issues impacting upon junior doctor morale in a large, multisite teaching hospital. We have described the complex relationship between how supported, autonomous and valued our junior doctors feel, and identified a number of key factors contributing to the morale of junior doctors.

Doctors identified ‘feeling part of a team’ as the most significant factor to positively affect their morale. Erosion of the traditional medical team structure has made it more difficult for doctors to create secure working relationships.1 Senior trainees indicated that they felt better supported than more junior doctors, which may be due to the rotational nature of training programmes and short placements in many provider units, which can make it challenging for junior doctors to feel embedded and supported by their teams and employing organisations. It is important that doctors feel valued, working as part of a supportive team. Despite the challenges of new working patterns and changing healthcare teams, we need to endeavour to find new ways to embed junior doctors within a team culture.

Being recognised and rewarded for good practice was highly ranked by junior doctors as a positive factor towards maintaining good morale. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs identifies that people require their basic physiological needs to be met and to have a sense of safety, belonging and self-esteem.9 A lack of availability of basic resources, including parking facilities, rest areas, payroll issues and inadequate administrative support, were cited as contributing to low morale. Previously, authors have identified that the availability of such resources is key to engendering a positive workplace environment.1,3,7

Doctors who indicated that they had experienced distressing encounters with clinical or managerial colleagues stated that this adversely affected their morale. Suboptimal relationships between doctors and managers in the NHS has been recognised1 as a pervasive problem in healthcare that should be improved.

A desire for a greater degree of autonomy was reported by some senior trainees, who felt over-supervised. Conversely, some junior doctors reported that they had too much imposed autonomy during instances of understaffing or rota gaps.

Working in a pressured environment is leading doctors to focus more upon their personal health and wellbeing.2 Multiple authors have identified key components1,2,7,8 that are important to wellbeing in the workplace including: a supportive culture; communicating with engaged leadership; functional multidisciplinary teams; easing administrative challenges; and, policies that enhance wellbeing. Many of these factors were echoed in the themes we have identified.

Our survey results suggest that to improve junior doctors’ sense of feeling valued, there is a need for organisations to recognise and reward junior doctors’ good work and to ensure basic workplace resource requirements are provided, e.g. parking, availability of rest rooms, etc. As Scanlan et al.10 reported, perceived organisational support is a key factor in influencing junior doctors’ career choices and decisions to remain within the NHS medical workforce. The atmosphere within which an employee works, influences whether they have low or high morale.11 The major themes that emerged from our qualitative analysis are those that are conducive to a good workplace atmosphere, such as being supported by senior clinicians and the wider team, working as part of an effective team and a culture of positive feedback.

The study has some limitations. First, respondents who had more negative experiences are more likely to respond to a survey, and may focus on their negative experiences. To minimise survey bias, we explicitly sought both positive and negative responses to questions. Second, most junior doctors rotate between posts every 4 months and remain within a single Trust for 1 year. This survey may have captured perspectives mostly from the current post rather than their experience as a whole. Third, this survey was conducted from November to December, thus the impact of increased workload during winter pressures may have influenced responses, particularly relating to staffing and workload.

In conclusion, the present survey highlights the importance of listening to junior doctors and engaging with them to identify improvements to improve their wellbeing and working lives. The survey therefore has provided an opportunity for development of a series of targeted interventions based upon the key themes to improve the working lives for junior doctors in our hospital. This has led to the formulation of an improvement campaign, the impact of which shall be evaluated in due course.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank NHS Staff Surveys for permission to use a selection of questions. We would also like to thank Professor Sheona MacLeod and Dr Shiv Chande for their guidance in development of the questionnaire.

Online Supplementary Material

Appendix 1 is available with the online version of this paper, which can be accessed at https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/journal.

References

1 Royal College of Physicians. Being a junior doctor: experiences from the front line of the NHS. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/being-junior-doctor (accessed 07/06/18).

2 GMC. The state of medical education and practice in the UK. 2018. https://www.gmc-uk.org/about/what-we-do-and-why/data-and-research/the-state-of-medical-education-and-practice-in-the-uk (accessed 11/12/18).

3 Health Education England. Junior doctor morale. Understanding best practice working environment. 2017. https://hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Junior Doctors%27 Morale - understanding best practice working environments_0.pdf (accessed 07/06/18).

4 Health Education England. Facing the facts, shaping the future a draft health and care workforce strategy for England to 2027. 2017. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Facing the Facts%2C Shaping the Future – a draft health and care workforce strategy for England to 2027.pdf (accessed 11/01/19).

5 UK Foundation Programme. Careers Destination Report 2017. https://www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/2018-07/2017%20F2%20Career%20Destinations%20Report_0.pdf (accessed 26/08/19).

6 GMC. Training pathways 2: why do doctors take breaks from their training? 2018. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/dc11392-training-pathways-report_pdf-75268632.pdf (accessed date 11/12/18).

7 Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management, NHS Providers, NHS Improvement. Eight high impact actions to improve the working environment for junior doctors. 2017. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/eight-high-impact-actions-to-improve-the-working-environment-for-junior-doctors/ (accessed 10/06/18).

8 Health Education England. Enhancing junior doctors’ working lives. A progress report. 2018. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Enhancing junior doctors working lives - a progress report.pdf (accessed 12/01/19).

9 Maslow AH. A Theory of Human Motivation. Originally Published in Psychological Review, 50, 370-396. Classics in the History of Psychology: An internet resource developed by Christopher D. Green. York University, Toronto, Ontario. Posted August 2000. 1943. https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm (accessed 21/11/18).

10 Scanlan GM, Cleland J, Walker K et al. Does perceived organisational support influence career intentions? The qualitative stories shared by UK early career doctors. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e022833.

11 Yoder D. Personnel Management and Industrial Relations. New York: Prentice-Hall; 1942.