GENDER

Admissions

The publicity material of the Edinburgh dispensary emphasised that it aimed to cater for both men and women equally. In cases ‘where a father may still provide for those of his house’ it assisted him by providing outpatient care. But it was equally important to the mother who ‘tend[ed] her helpless infants’.

Because the Edinburgh infirmary barred women with young children from admission (blaming, in part, the noise they would make on the wards) that meant that the city’s dispensary was particularly important for that group.

Physical examination

Stereotypes around patient treatment in the eighteenth century have created the idea that only surgeons touched and physically examined patients, especially female patients. Physicians, according to this logic, were ‘thinkers, not touchers’. They were concerned with the modesty and dignity of their female patients. Instead, they read books, talked to their patients, and espoused theories.

In the Edinburgh dispensary, physicians often used percussive sounding on their female patients and examined female patient’s bodies, including identifying a tumour in a female patient’s breast by touch [DEP/DUA/1/12/03].

Menstruation

Over a third of the women in these case notes had issues relating to menstruation – either irregular or excessive menstruation. Or, in some cases, a related symptom called fluor albus (a form of vaginal discharge, also known as ‘the whites’). Low weight, poor nutrition, infertility and previous difficult births all played a part in this. One woman, 40-year-old Isabel Campbell was described as suffering from a ‘constant discharge from the vagina of a considerable quantity of thick viscid, whitish coloured matter’.

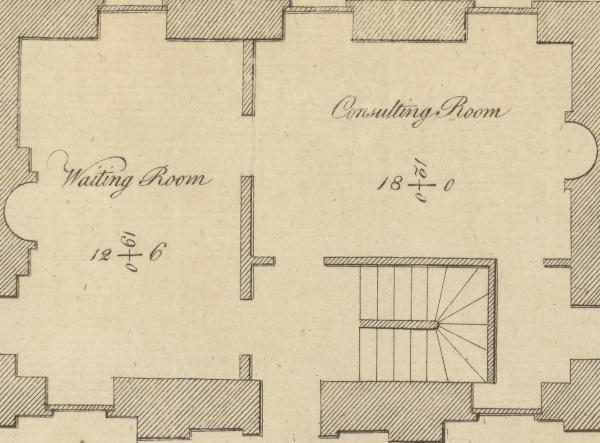

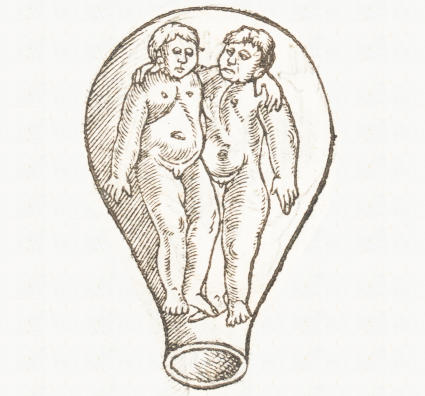

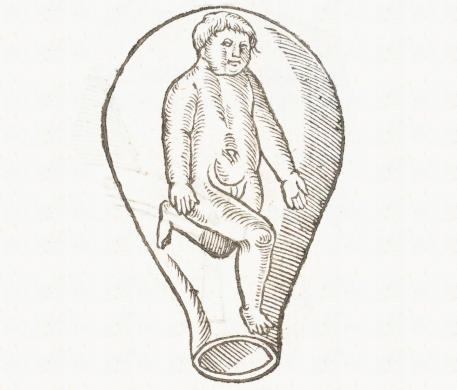

Pregnancy

If poor women in the eighteenth century often had problems relating to menstruation, how could a medical practitioner accurately identify when their patient was pregnant? Many medicines at this time were very aggressive and caused vomiting and diarrhoea. They could also be dangerous to an unborn child and the dispensary physicians were very concerned about this risk. They often prescribed mild or ineffective medicines until they could be sure if their patient was pregnant or not.

Edinburgh dispensary physicians registered concern on a number of occasions that patients may have been disguising their pregnancy and falsifying a separate medical condition in an attempt to procure treatment that would bring about the ‘restor[ation] of mens[truation] [and] abort[ion] [would thereby be] prod[uced]’ [DEP/DUA/1/40/52].

Hysteria

Symptoms of hysteria ranged from fits to emotional distress, dizziness, paralysis, constipation, difficulty breathing, and depression. The wide variety of symptoms of hysteria and the ambiguity in its diagnosis led dispensary physicians to often be suspicious of patients who were diagnosed with hysteria.

In the case of 29 year old Mary Rawlinson who was admitted to the Edinburgh dispensary in the spring of 1782, according to Andrew Duncan’s notes, although the symptoms which were described ‘might in some degree exist’, he ‘yet had reason to pres[ume] that [they] were to no great degree & that [the] patient[’s] repres[entation] of [the] affect [is] rather exaggerated’. Duncan went even further in another case, arguing that ‘hyster[ia] symp[toms] [are] often feign[e]d… many female[s]… [are] not only capab[le] of very exact imit[ation] of fits but even of induc[ing] real fits when necess[ary]’ [DEP/DUA/1/30/24].