-

Medicines Online Exhibition

-

-

Simples

Medical simples were just that, simple. They were not complex or compound medicines, they weren’t made by combining a range of ingredients. The word ‘simple’ or ‘simples’ was used in different ways – sometimes it referred just to herbal medicines, sometimes it meant any type of medicine that was taken pure, without mixing it with anything else. Others referred to simples as the raw ingredients which would be prepared, and then later would be combined with other ingredients by a physician or apothecary before supplying it to the patient.

Simples were the most common, and most easily available, form of medicine. They were given to the sick poor, for free, in towns and villages across the Highlands and Islands – including Golspie, Stornoway and the Isle of Arran.

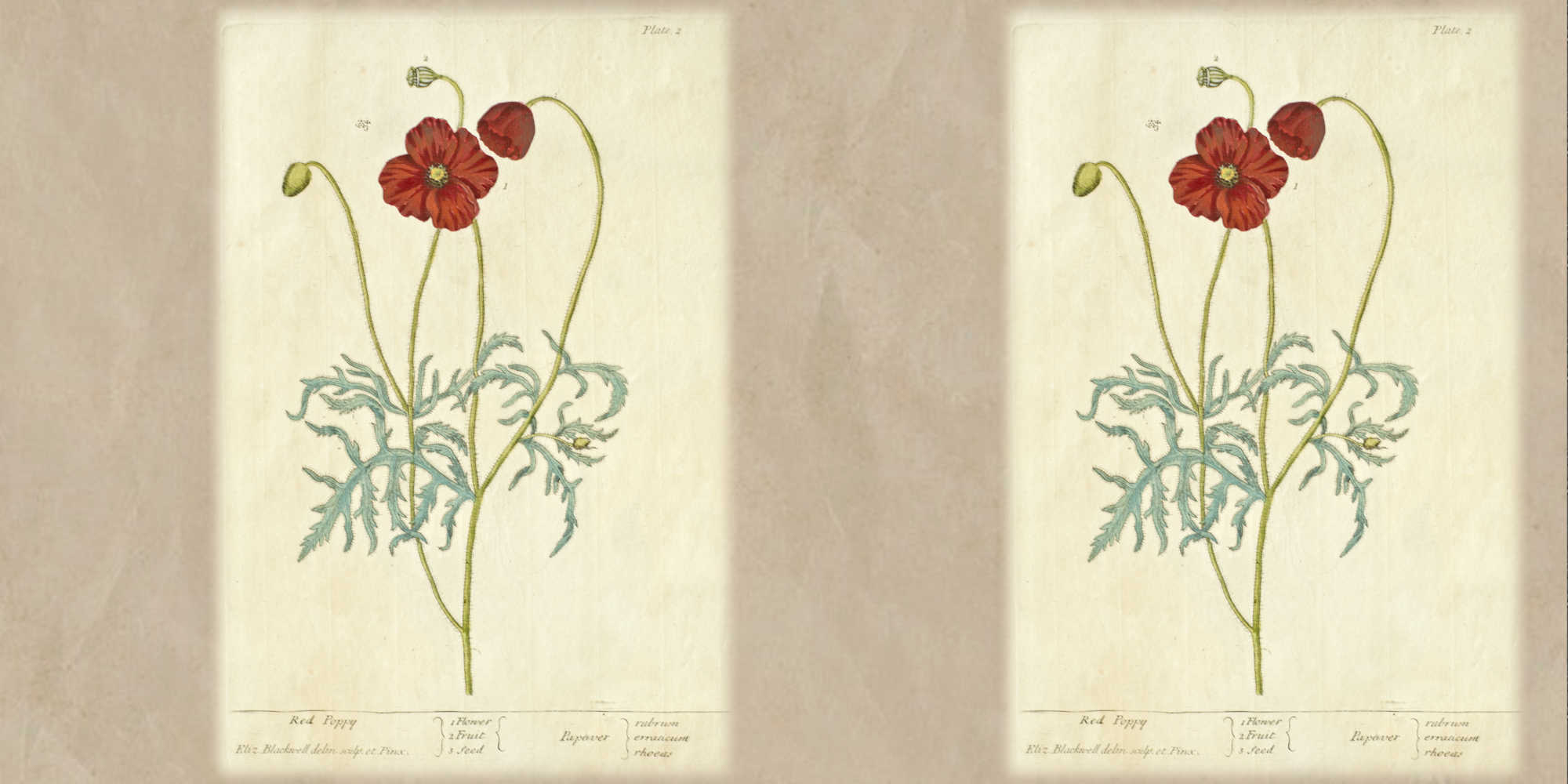

Image: A curious herbal, Elizabeth Blackwell (1730s)

-

-

"In the Manse & two other families, the simplest domestic medicines are gratuitously furnished to applicants, with any simple directions for treatment that can be given, in cases of emergency"

(William MacRae, Barvas, Isle of Lewis)

-

-

Castor Oil

Castor oil, a yellow liquid distilled from castor beans, was one of the most common simples. According to one Inverness Reverend ‘almost everybody’ could advise on the correct dose of castor oil. In Golspie it was available from the local grocer.

This was one of the cheapest, and most easily accessible, forms of medicine. In the 1800s it was seen as a miracle cure for almost every ailment and was often prescribed to help with constipation, heartburn and as a means of inducing labour. Due to its use as a quick-working laxative, castor oil was sometimes used as a humiliating punishment, notably in Fascist Italy when Mussolini’s power was said to be backed by ‘the bludgeon and castor oil’.

Image: Bottle of Castor Oil (1800s)

-

-

-

Rhubarb

Rhubarb was another very common medicine in the 1700s and 1800s. Although it was grown in Scotland by the 1800s, there were sometimes shortages and one Reverend in Thurso complained that there was not enough to treat the local sick poor.

Originating in China and India, it is said that the first European account of rhubarb was in the notes of Marco Polo. It was prescribed as a vomit and laxative and considered gentler than many other herbal remedies of the time. In its powdered form, it was used as an ingredient in medicines for constipation such as Gregory’s Powder.

Image: Bottle of Gregory’s Powder (1800s)

-

-

"When I settled here, & for many years after, the medical man had all the dispensing of medicine. Now there are druggists, who interfere very much with the emoluments of the professional men"

(Dr Duguid, Kirkwall, Orkney)

-

-

Quinine

Quinine is a medical ingredient which can be found in Peruvian Bark. As the name suggests, this bark was extracted from trees in South America. This medicine was first brought to Europe in the 1600s. Counterfeit bark was common as it sold for a high price and there was no accurate way to test the bark to see if it was the right type.

It was an effective treatment for malaria but doctors also tried to use it, much less effectively, on a wide range of other diseases – from cholera and smallpox to difficult labours and sore legs.

Quinine was mixed with tonic water in British India and the bitter taste prompted colonials to mix it with gin, creating the Gin and Tonic.

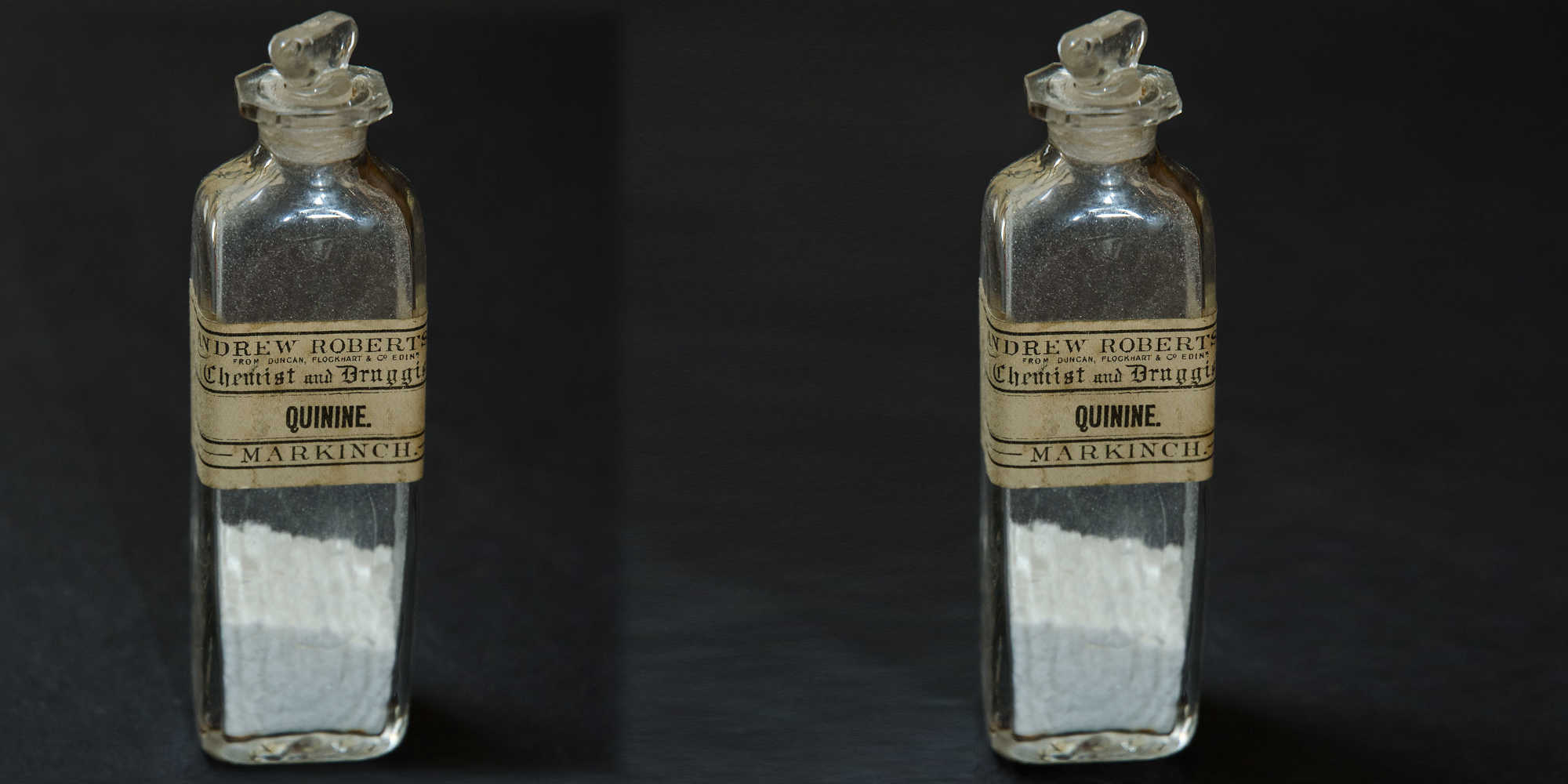

Image: Bottle of Quinine (1800s)

-

-

"Sometimes – not foreseeing the cases which may arise, and being provided only with a supply of the more common medicines – I find myself hampered in my efforts for the restoration of afflicted ones – so that not only our deficiency of medical knowledge but our utter inability at times to obtain in due season the medicines which we desiderate operates as a hindrance to our success"

(Robert Wilson, Kirkwall, Orkney)

-

-

Blisters

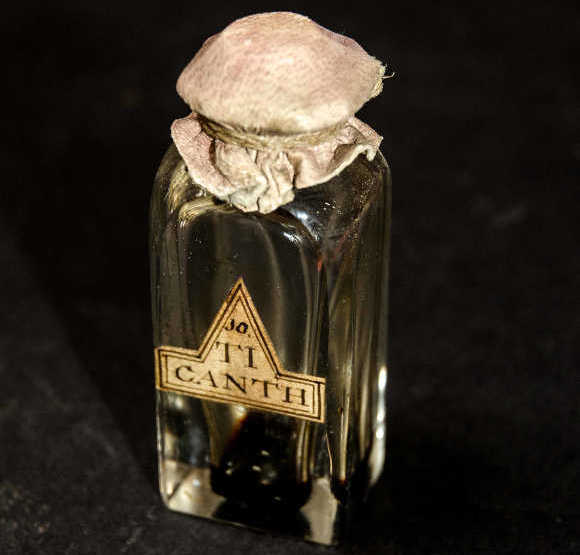

Blisters weren’t a medicine as such, they were a form of treatment – a process which was carried out on the body. Medicine in the form of a blistering agent, however, was needed to successfully bring about the blisters.

Early medical theory around blistering was similar to that of bloodletting – it would rebalance the body and remove anything unhealthy or excessive contained in it.

The process of blistering usually involved the application to the skin of a plaster which was coated with an irritant, such as mustard or onion. Another common blistering agent was made from crushed Blister Beetle shells, known as Cantharides, which is shown here. The resulting blister could then be left to heal or could be continually irritated to create a constant weeping sore, known as an ‘issue’.

Bottle of Cantharides (1700s)

-

-

Medicines Online Exhibition

-

Simples

Medical simples were just that, simple. They were not complex or compound medicines, they weren’t made by combining a range of ingredients. The word ‘simple’ or ‘simples’ was used in different ways – sometimes it referred just to herbal medicines, sometimes it meant any type of medicine that was taken pure, without mixing it with anything else. Others referred to simples as the raw ingredients which would be prepared, and then later would be combined with other ingredients by a physician or apothecary before supplying it to the patient.

Simples were the most common, and most easily available, form of medicine. They were given to the sick poor, for free, in towns and villages across the Highlands and Islands – including Golspie, Stornoway and the Isle of Arran.

Image: A curious herbal, Elizabeth Blackwell (1730s)

-

"In the Manse & two other families, the simplest domestic medicines are gratuitously furnished to applicants, with any simple directions for treatment that can be given, in cases of emergency"

(William MacRae, Barvas, Isle of Lewis)

-

Castor Oil

Castor oil, a yellow liquid distilled from castor beans, was one of the most common simples. According to one Inverness Reverend ‘almost everybody’ could advise on the correct dose of castor oil. In Golspie it was available from the local grocer.

This was one of the cheapest, and most easily accessible, forms of medicine. In the 1800s it was seen as a miracle cure for almost every ailment and was often prescribed to help with constipation, heartburn and as a means of inducing labour. Due to its use as a quick-working laxative, castor oil was sometimes used as a humiliating punishment, notably in Fascist Italy when Mussolini’s power was said to be backed by ‘the bludgeon and castor oil’.

Image: Bottle of Castor Oil (1800s)

-

Rhubarb

Rhubarb was another very common medicine in the 1700s and 1800s. Although it was grown in Scotland by the 1800s, there were sometimes shortages and one Reverend in Thurso complained that there was not enough to treat the local sick poor.

Originating in China and India, it is said that the first European account of rhubarb was in the notes of Marco Polo. It was prescribed as a vomit and laxative and considered gentler than many other herbal remedies of the time. In its powdered form, it was used as an ingredient in medicines for constipation such as Gregory’s Powder.

Image: Bottle of Gregory’s Powder (1800s)

-

"When I settled here, & for many years after, the medical man had all the dispensing of medicine. Now there are druggists, who interfere very much with the emoluments of the professional men"

(Dr Duguid, Kirkwall, Orkney)

-

Quinine

Quinine is a medical ingredient which can be found in Peruvian Bark. As the name suggests, this bark was extracted from trees in South America. This medicine was first brought to Europe in the 1600s. Counterfeit bark was common as it sold for a high price and there was no accurate way to test the bark to see if it was the right type.

It was an effective treatment for malaria but doctors also tried to use it, much less effectively, on a wide range of other diseases – from cholera and smallpox to difficult labours and sore legs.

Quinine was mixed with tonic water in British India and the bitter taste prompted colonials to mix it with gin, creating the Gin and Tonic.

Image: Bottle of Quinine (1800s)

-

"Sometimes – not foreseeing the cases which may arise, and being provided only with a supply of the more common medicines – I find myself hampered in my efforts for the restoration of afflicted ones – so that not only our deficiency of medical knowledge but our utter inability at times to obtain in due season the medicines which we desiderate operates as a hindrance to our success"

(Robert Wilson, Kirkwall, Orkney)

-

Blisters

Blisters weren’t a medicine as such, they were a form of treatment – a process which was carried out on the body. Medicine in the form of a blistering agent, however, was needed to successfully bring about the blisters.

Early medical theory around blistering was similar to that of bloodletting – it would rebalance the body and remove anything unhealthy or excessive contained in it.

The process of blistering usually involved the application to the skin of a plaster which was coated with an irritant, such as mustard or onion. Another common blistering agent was made from crushed Blister Beetle shells, known as Cantharides, which is shown here. The resulting blister could then be left to heal or could be continually irritated to create a constant weeping sore, known as an ‘issue’.

Bottle of Cantharides (1700s)