-

Bloodletting Online Exhibition

-

-

The origins of ideas around bloodletting lie within the humoural system, which dates back to at least the time of Ancient Egypt. From there it spread to Ancient Greece where many physicians, including Erasistratus, concluded that all disease was the result of an excess of blood.

The humoural system is quite complex. Although the principles were changed and adapted over time, essentially, according to this idea, there were four humours in the body: yellow bile, black bile (also known as choler), phlegm and blood.

Image: Erasistratus the physician, discovers the love of Antiochus for Stratonice, Valentine Green (1776)

-

-

-

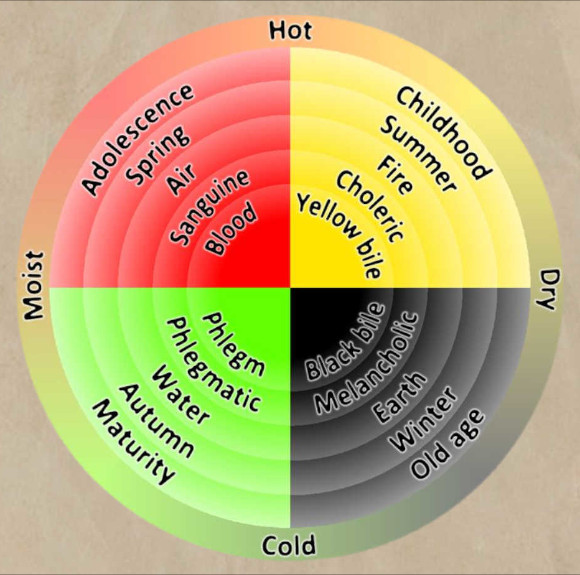

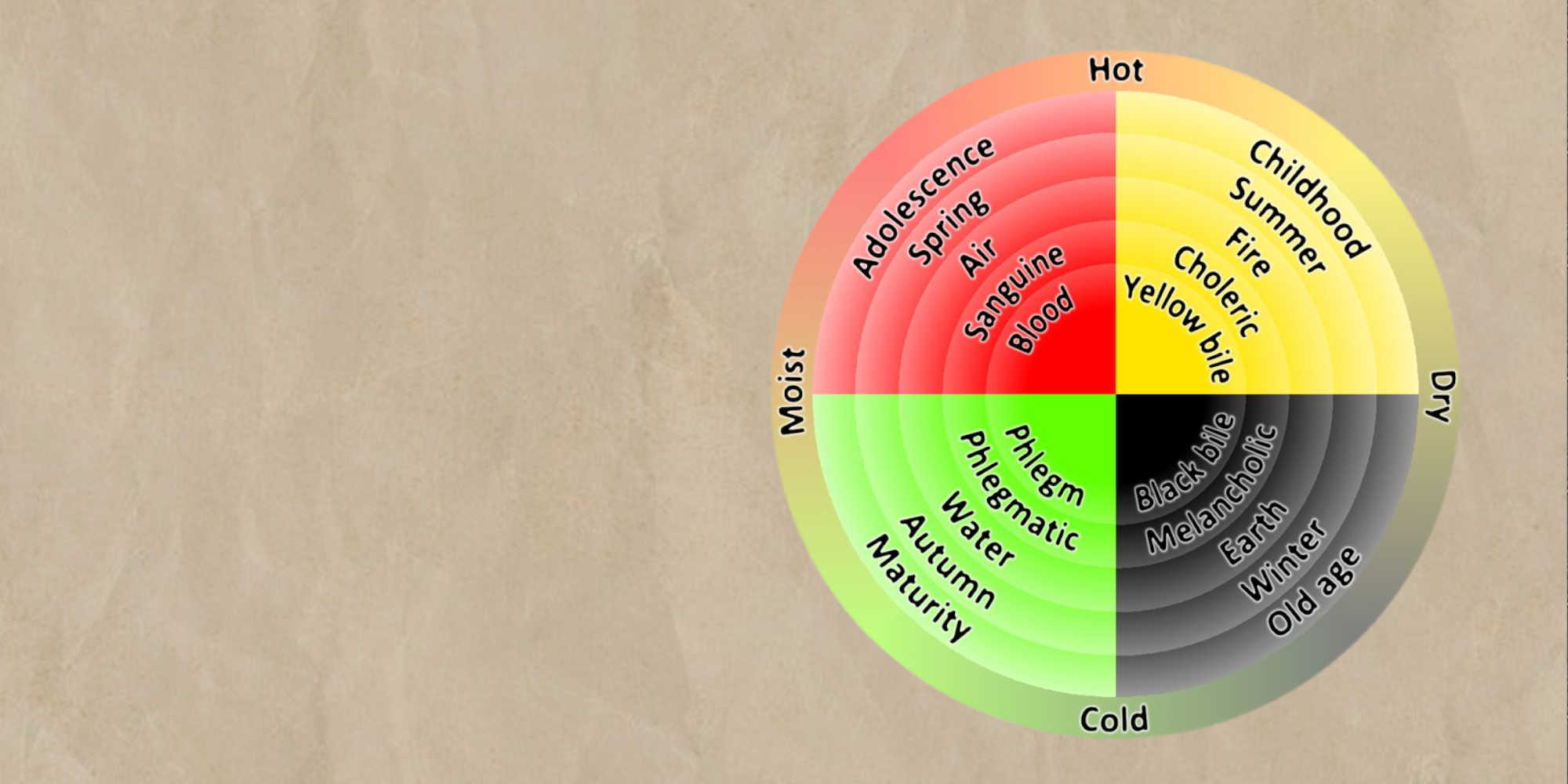

Alongside these humours, there were four corresponding temperaments - you could be phlegmatic, choleric, sanguine or melancholy. These corresponded with the four elements (earth, air, fire and water), the four seasons (Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter), the four ages of man (childhood, adolescence, maturity and old age) and hot, cold, moist and dry.

So maintaining health was all about balancing these four humours. If you were ill that meant your humours were out of balance. A person could have too much humoural blood and so bleeding would make them more balanced – it would make them colder and drier.

Image: Diagram demonstrating humoural system

-

-

"There are two men in the place who can bleed – but they have very bad lancets. They have often done much good, and I do not hear of a case in which bleeding was resorted to which a medical man did not approve of bleeding"

(Angus Macintyre, Oban)

-

-

Bloodletting became the standard treatment for a wide range of diseases – from plague, cancer and smallpox, to rheumatism, acne and headaches.

Bloodletting took different forms. Leeches could be applied to the skin. Where the leech was placed depended on where the disease was located – headaches, for example, meant a leech was placed on the face.

Leeches were so popular in the 1800s that Britain imported over six million leeches every year.

Image: Leech encased in resin (2020)

-

-

-

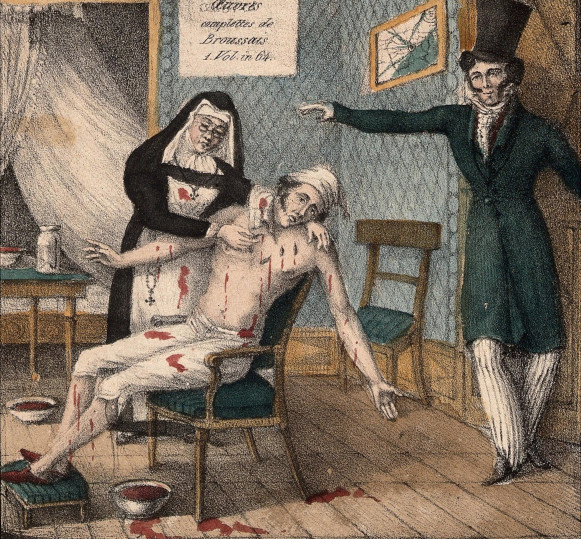

Another method was ‘cupping’ during which the patient’s skin was punctured by a lancet or other sharp tool and then their blood collected in a cup or bowl.

Doctors often recommended what they called ‘heroic bleeding’ – which meant bleeding a patient until they became weak and unable to move. Often the bleeding was only stopped when the patient fainted from the blood loss.

Image: Bleeding bowls (1800s)

-

-

"I know of one (medical emergency) which has occurred very lately. It was that of a young man taken suddenly ill of some inward complaint His mother applied to an ignorant fellow in the neighbourhood who came & bled him profusely in consequence of which his complaint assumed a new and more formidable aspect & under which he succumbed at last"

(Donald Sage, Resolis)

-

-

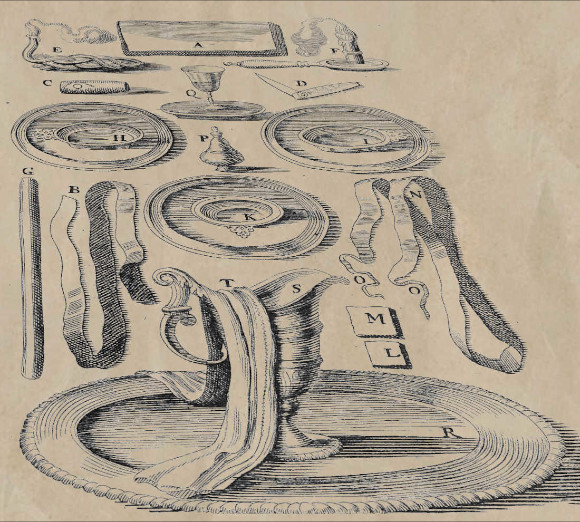

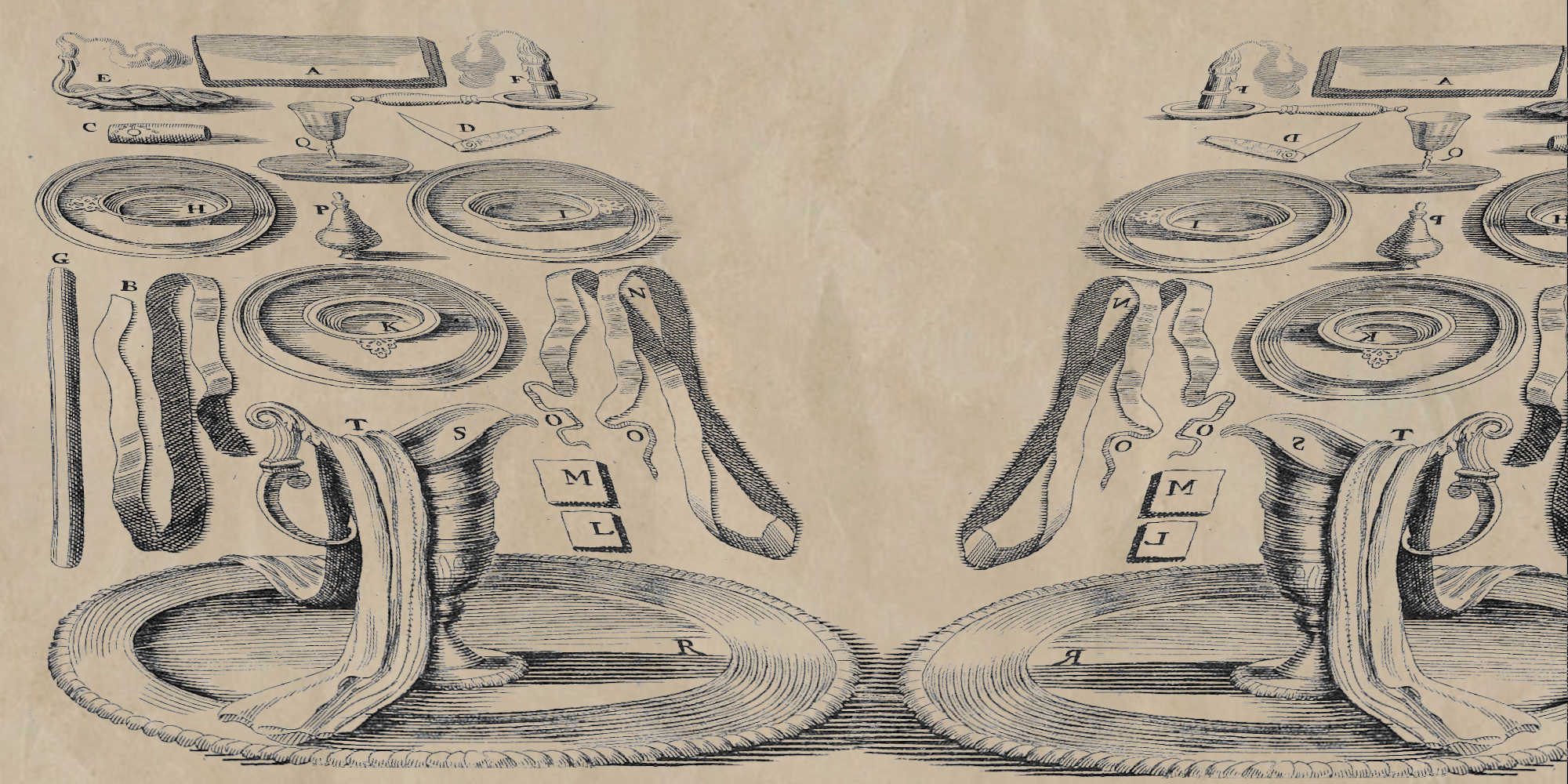

This image shows a range of bloodletting equipment which was in use in the 1800s, including lancets and cups.

During the 1700s and 1800s belief in humoural theory declined, doctors turning to other, more progressive-seeming methods of treatment. Bleeding however still remained. Different ideas were put forward as to why it was useful – perhaps it calmed the patient, or generally cleansed the system and removed ‘bad’ or diseased blood. As doctors became cautious and more selective in their use of bleeding, bloodletting increasingly became the work of folk healers or unqualified practitioners.

Image: A Course of Chirurgical Operations, Pierre onis (1708)

-

-

-

Bleeding is the most common form of medical treatment mentioned in the Highlands and Islands surveys. In Daviot, Inverness, there were ‘a few men who can draw blood’. In Golspie there were ‘2 or 3 who can use the lancet’. Not everyone thought that the bloodletting of unqualified healers was necessarily helpful. The Reverend Donald MacRae, in Stornoway, noted that two men there ‘use the lancet perhaps too often’. In another cautionary tale, from a village near Inverness, ‘free use of the lancet’ was made by two ‘uneducated men’.

-

-

Bloodletting Online Exhibition

-

The origins of ideas around bloodletting lie within the humoural system, which dates back to at least the time of Ancient Egypt. From there it spread to Ancient Greece where many physicians, including Erasistratus, concluded that all disease was the result of an excess of blood.

The humoural system is quite complex. Although the principles were changed and adapted over time, essentially, according to this idea, there were four humours in the body: yellow bile, black bile (also known as choler), phlegm and blood.

Image: Erasistratus the physician, discovers the love of Antiochus for Stratonice, Valentine Green (1776)

-

Alongside these humours, there were four corresponding temperaments - you could be phlegmatic, choleric, sanguine or melancholy. These corresponded with the four elements (earth, air, fire and water), the four seasons (Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter), the four ages of man (childhood, adolescence, maturity and old age) and hot, cold, moist and dry.

So maintaining health was all about balancing these four humours. If you were ill that meant your humours were out of balance. A person could have too much humoural blood and so bleeding would make them more balanced – it would make them colder and drier.

Image: Diagram demonstrating humoural system

-

"There are two men in the place who can bleed – but they have very bad lancets. They have often done much good, and I do not hear of a case in which bleeding was resorted to which a medical man did not approve of bleeding"

(Angus Macintyre, Oban)

-

Bloodletting became the standard treatment for a wide range of diseases – from plague, cancer and smallpox, to rheumatism, acne and headaches.

Bloodletting took different forms. Leeches could be applied to the skin. Where the leech was placed depended on where the disease was located – headaches, for example, meant a leech was placed on the face.

Leeches were so popular in the 1800s that Britain imported over six million leeches every year.

Image: Leech encased in resin (2020)

-

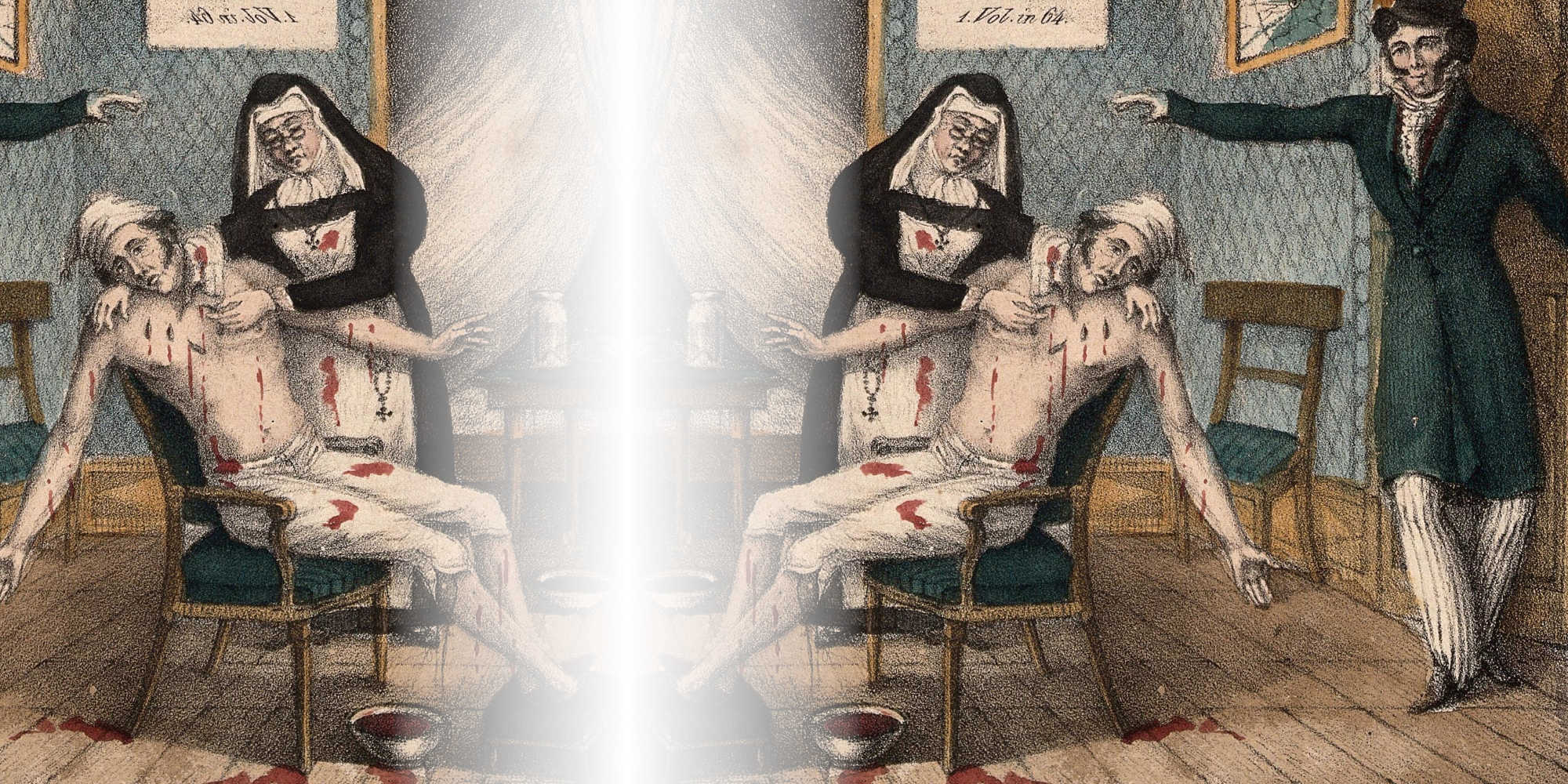

Another method was ‘cupping’ during which the patient’s skin was punctured by a lancet or other sharp tool and then their blood collected in a cup or bowl.

Doctors often recommended what they called ‘heroic bleeding’ – which meant bleeding a patient until they became weak and unable to move. Often the bleeding was only stopped when the patient fainted from the blood loss.

Image: Bleeding bowls (1800s)

-

"I know of one (medical emergency) which has occurred very lately. It was that of a young man taken suddenly ill of some inward complaint His mother applied to an ignorant fellow in the neighbourhood who came & bled him profusely in consequence of which his complaint assumed a new and more formidable aspect & under which he succumbed at last"

(Donald Sage, Resolis)

-

This image shows a range of bloodletting equipment which was in use in the 1800s, including lancets and cups.

During the 1700s and 1800s belief in humoural theory declined, doctors turning to other, more progressive-seeming methods of treatment. Bleeding however still remained. Different ideas were put forward as to why it was useful – perhaps it calmed the patient, or generally cleansed the system and removed ‘bad’ or diseased blood. As doctors became cautious and more selective in their use of bleeding, bloodletting increasingly became the work of folk healers or unqualified practitioners.

Image: A Course of Chirurgical Operations, Pierre onis (1708)

-

Bleeding is the most common form of medical treatment mentioned in the Highlands and Islands surveys. In Daviot, Inverness, there were ‘a few men who can draw blood’. In Golspie there were ‘2 or 3 who can use the lancet’. Not everyone thought that the bloodletting of unqualified healers was necessarily helpful. The Reverend Donald MacRae, in Stornoway, noted that two men there ‘use the lancet perhaps too often’. In another cautionary tale, from a village near Inverness, ‘free use of the lancet’ was made by two ‘uneducated men’.

Image: Broussais instructs a nurse to carry on bleeding a blood-besmeared patient, V.L. (1830s) Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0) Image source