THERAPEUTICS

Bleeding, blistering, and bathing were commonly prescribed treatments in the 1700s and were all techniques which had been in use in western medicine since antiquity.

Bathing

Bathing was not a treatment which was reserved exclusively for the rich, although bathing for medicinal purposes by the poor rarely took place in such pleasant surroundings such as those of the towns of Bath or Leamington Spa. Instead, it took place in local rivers, in the open sea, or in tubs in their own homes.

While baths which were open to the general public were erected in many towns and cities in Britain during the 1700s, either as private enterprises or attached to infirmaries, the fees commonly charged for their use restricted their accessibility to the poor. Sea bathing, however, carried with it attendant risks. In the case of Margaret Gray, a patient admitted to the Edinburgh dispensary in the winter of 1781 with a diagnosis of hysteria, it was recommend that she bathe in a tub or ‘form of shower bath’ rather than sea bathing, because ‘in deep water fatal conseq[uences] in [the] way of drown[ing] have sometim[es] hap[pened]’ [DEP/DUA/1/27/12].

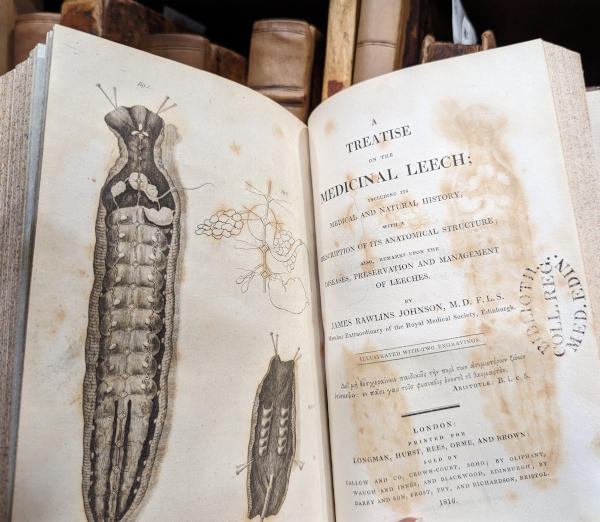

Bloodletting

Bloodletting could take multiple forms. It included the application of leeches, but also cupping, by which the patient’s skin was punctured and then their blood collected in a cup or other receptacle.

In the case of the Edinburgh dispensary’s patients, while it was believed that cupping was more effective, they were ‘obliged to give pref[erence]’ to the use of leeches, ‘as from being more famil[iar] [with this] patients [are] less afraid of it’ [DEP/DUA/1/27/15].

Bloodletting was used at the dispensary as a treatment for a range of conditions, including fever and asthma.

Blistering

The process of blistering commonly entailed the application to a patient’s skin of a plaster which was coated with an irritant, such as mustard or onion. The resulting blister was then either left to heal or could be continually irritated to create a constant weeping sore, known as an ‘issue’.

Blistering was used at the dispensary to treat a wide array of conditions, from respiratory complaints, rheumatism, and fungal infections to paralysis.

Definition:

The term ‘placebo’ is used multiple times in the case notes. It is clear from its use though, that this term isn’t being used in the twenty-first-century sense. There is no idea that there will be a psychological benefit for the patient, but rather that using an inert or superfluous medicine would encourage the patient to keep visiting the dispensary, so allowing the physician to observe the outcome of their case.

Blistering, however, was a particularly unpopular method of treatment amongst dispensary patients and the prescription of blisters often resulted in either a patient’s refusal to accept that method of treatment or their ceasing attendance altogether.

Electricity

Over the course of the 1700s, electricity became a subject of fascination and of both public and private entertainment. The use of electricity for medical purposes began to be studied in the 1740s and, by the 1770s, it was considered by many to be a standard component of a physician’s medical practice.

The Edinburgh dispensary owned an electrical machine. These machines could take a variety of forms, commonly involving a glass jar which collected the electrical charge, known as a Leyden jar, and a hand crank which caused the necessary friction to build the static charge.

Electricity could be administered to the patient in a number of different ways. It could be applied to the patient’s whole body using a technique known as ‘insulation’, where an electrical charge was applied to a chair, bench, or bed which the patient was reclining on. It could also be introduced more locally to the patient’s body through shocks or sparks created by transferring the electricity to the patient via a metal conductor, which would either be placed on the skin or grasped in the patient’s hand. Devices could be small enough to be easily carried around or large, immobile pieces of equipment.

The Edinburgh dispensary’s physicians were extremely enthusiastic about the use of electricity on their patients. It was noted in the dispensary records that ‘a good electr[icity] machine [is] a part of medic[al] appar[a]t[us] which every practit[ioner] should possess’ [DEP/DUA/1/18/06]. The dispensary’s electrical machine was used on many different conditions, including tumours and sore necks, to restore failing eyesight and to encourage menstruation. But, like with blistering, many patients were not keen to undergo treatment by electricity and were ‘much afraid of it’ [DEP/DUA/1/22/02].